Rosewood descendant to speak at CF

Lizzie Robinson Jenkins will share her family’s memories of the 1923 massacre.

Jan. 1, 2023, will mark the 100th anniversary of the Rosewood massacre in nearby Levy County. On Oct. 18, the College of Central Florida will host Lizzie Robinson Jenkins, founder of the Real Rosewood Foundation, who will share the stories of Rosewood that stayed secret for decades and explain why it is crucial to remember this event 100 years later.

According to historical records and personal statements, Rosewood was settled in 1845 by Blacks and whites. The town was reportedly named for the red cedar trees in the area and the rose-like scent the wood had when freshly cut. The wood was often cut for making pencils. Around 1890, the cedar tree population was decimated and many of the white families moved away. By the 1920s, Rosewood’s population of between 200 and 300 was mostly made up of Black citizens who owned their own homes, established businesses and farmed. One white family, the Wrights, operated a general store and made their home there.

On New Year’s Day 1923, Fannie Taylor, 22, who was white, alleged that a Black man entered her home and beat her. A recently escaped Black convict was assumed to be that man. Taylor’s husband gathered an angry mob of white citizens and used dogs to track the man. This led them to Rosewood, where several men were accused of aiding and concealing the alleged attacker.

One Black resident was lynched and another was beaten and dragged behind a car. That man’s aunt, Sarah Carrier, the matriarch of Rosewood’s most prominent family, who worked as a laundress for the Taylors, said she had seen Mrs. Taylor’s assailant at their home that day and that he was a white man who she had seen there before.

The theory that Mrs. Taylor was having an affair and used the claim of being attacked by a Black man has long been the prevailing notion and was widely reported. There is no record, however, that she ever recanted her story.

On Jan. 4, a mob of about 30 men descended on Carrier’s home, where numerous relatives were staying, and shot her dead and sprayed the house with gunfire. They kicked in the front door but her son, Sylvester, fended them off by killing two of the men and wounding four others. Once the mob retreated, he sent the women and children to hide in the swamp.

Newspapers reported on the standoff, exaggerating the number dead and falsely reporting that groups of armed Black citizens had gone on a rampage. White men poured into the area, including about 500 Ku Klux Klan members who were in Gainesville for a rally. Newspaper reports from the time say the mob engaged in a “race riot” with lynchings, shootings, mutilations, burnings and mass graves, though in reality it was more of an extermination, with whites hunting Blacks mercilessly. The carnage lasted for seven days.

Many of the women and children stayed hidden in the swamps and woods for days, while others were concealed in the home of the white general store owner John Wright. Wright was able to convince John and William Bryce, two wealthy white brothers who owned a train, to pick up terrified women and children and take them to safety. Any adult men who made it out did so on foot.

On Jan. 7, the mob returned and burned everything that remained of Rosewood to the ground, except for the home of John Wright.

According to the State of Florida, the official death toll was eight: six Blacks and two whites. Rosewood survivors, however, believe the numbers on both sides to be higher, believing that at least 150 Blacks were killed, which was supported by interviews with some of the whites who witnessed the events.

The governor convened a grand jury and appointed a special prosecutor to investigate. Though the jury heard the testimonies of nearly 30 witnesses, who were mostly white, it was claimed they could not find enough evidence to pursue prosecution.

Following the initial news coverage, the story was rarely spoken about.

In 1982, a reporter for the “St. Petersburg Times,” while on an assignment to write about Cedar Key, began to investigate the history of Rosewood. His “investigative expose” brought national attention that led to a “60 Minutes” special and stories by many other news outlets.

In 1993, the Florida House of Representatives heard the testimony of the survivors of the massacre, who demanded restitution. Children at the time of the events, they were now in their 80s and 90s and were represented by a powerful law firm. One white witness joined them to testify on behalf of the victims.

The Florida Legislature passed Rosewood Claim Bill 591. It allocated $150,000 dollars of state funds to each to the nine living survivors who had come forward, approximately $2,000 each to their descendants, and set up a program to allow Rosewood descendants to attend college in Florida tuition-free. According to the “Washington Post,” between 1994 and 2020, 297 students have been granted Rosewood scholarships. The case is considered groundbreaking as the only time in history that a government, federal or state, has compensated victims of mass racial violence.

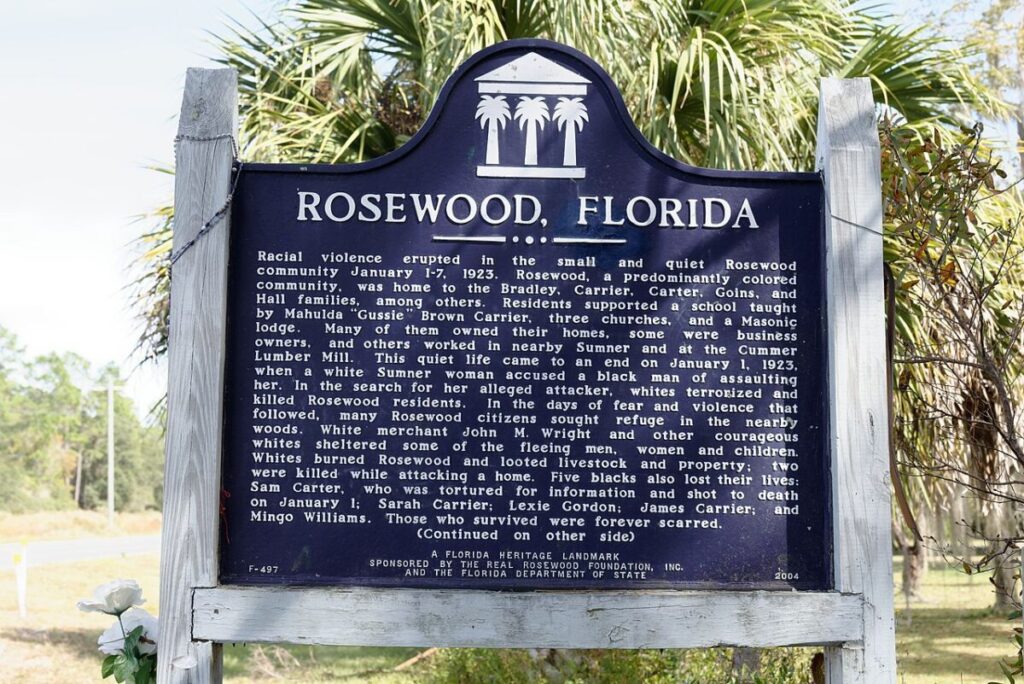

In 2004, Rosewood was designated as a Florida Heritage Landmark. All that remains of Rosewood today are the Wright home and a historical marker on State Road 24, just east of Cedar Key. Efforts to establish a Rosewood historic area and memorial heritage park are being pursued by The Rosewood Heritage Foundation, Inc. (rememberingrosewood.org).

Last year, the John Wright house was donated to the Real Rosewood Foundation (rosewoodflorida.com). The foundation is raising funds to have the house moved to a site in Archer, in Alachua County, where it will become a museum.

“We will protect and shelter the house, the same way the house sheltered the Rosewood survivors in 1923,” said Jenkins.

Jenkins’ Oct. 18 presentation is free and open to the public. It will begin at 6:30 p.m. in the Ewers Century Center, 3001 S.W. College Road, Ocala.

To learn more about CF, visit CF.edu.

Some information in this article came from an article by Nick Steele, published in the “Gazette” earlier this year, which you can read using clicking on this link.