When you give Marion County $63.7 million…

typewriter with paper sheet. Space for your text

When the federal government authorized billions for COVID-19 pandemic relief in March 2020, the money came with only three rules.

It had to be spent on pandemic-related expenses, the money could not pay for items already in budgets and expenses had to be run up between March 1 and December 30, 2020.

With only a few months to spend the money, the typical slow trod of government was supposed to go out the window.

But when Marion County got $63.7 million in Coronavirus Relief Funds (CRF) in July, the process wasn’t nimble enough and a month before the deadline they still had to find a way to qualify for the final $34 million under the rules.

Faced with the use-it or lose-it deadline, the county figured out a way to sweep the remaining money into its reserves by taking advantage of a loosening of the rules by the Department of Treasury allowing governments to use CRF to pay for already budgeted public health and safety employee payroll.

Eventually, the federal government extended the December deadline..

The county currently has more than $20 million unspent in the general fund.

Commission Chairman Jeff Gold said the money is being held for future vaccine or testing expenses.

“We’re holding it,” Gold said. “At this point we need to find out what’s going to come up, mostly with the vaccine. If this vaccine is a six-month vaccine… We’ll go back and re-open up our brick and mortar, we’ll pull in all these resources and we’ll get everybody vaccinated, where some of these other areas may have already spent that money. So, we’re holding it for that purpose, to make sure that everything’s safe because we just don’t know.”

But the original intent of the CRF was to get the relief money into the community quickly. Also, the county stands to receive another estimated $70 million from the most recent relief plan signed into law by President Joe Biden in March.

After reviewing thousands of invoices and the minutes of numerous government meetings, the Ocala Gazette explores how the county spent its share of the CRF, where the money went and where it didn’t.

In the beginning

As the COVID-19 pandemic quickly shutdown large swaths of the country, Congress passed, and President Donald Trump signed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act to try and bolster the economy. The law established the $150 billion Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) which went directly to the states.

Florida received more than $8.3 billion in CRF, with $3.75 billion going to local governments. Of the nearly $63.7 million Marion County received, it has spent about $40.6 million.

Originally the county established 10 areas where the money should go, including general government, emergency food distribution, housing assistance, human services assistance, small and medium-sized business grants, COVID-19 testing, non-congregate sheltering, re-employment training and broadband enhancements.

County commissioners then gave county administration the authority to execute the plan without the need for commission approval at public meetings.

Despite the attempt to streamline the process, not all categories were funded.

County Administrator Mounir Bouyounes said while some were not funded through the CRF program, they received funding through other means.

“Some of the categories were probably handled through a separate funding source,” Bouyounes said. “For example, non-congregate sheltering, I know we have handled those needs through the community services funding.”

For example, the county offered a contract to the United Way of Marion County to distribute $1 million in rental assistance using CRF, but Scott Quintel, president of the organization said the deadlines were tight and they didn’t have the capacity to disburse the money. The money was never spent on rental assistance.

Where the money went

Other than the county, the largest portion of the $63.7 million went to AdventHealth Ocala.

The non-profit hospital received about $11.8 million in reimbursements from costs incurred because of the pandemic.

The next largest amount was $7 million that went to business grants. That money was administered by the Ocala Metro Chamber & Economic Partnership.

Kevin Sheilley, CEP president and CEO, said the county did well in speeding up the wheels of government.

“Being able to pivot and to change is not something that we set up governments to do, they’re generally not very good at it,” Sheilley said. “And in this case, we were asking our governments to kind of do the exact opposite of what they’ve always been told to do, which was to try to move quickly and to quickly distribute the money… usually we’re trying to tell them to go slow and don’t give away money. So, I think for what it was, I think, compared to when I talk to people elsewhere, you know, we’ve handled it pretty good all around.”

The CEP’s goal was to focus on those most in need, even if that meant not every business would receive funding. Some didn’t finish the application, or the committee reviewing the application didn’t deem the company was significantly affected by the pandemic.

“It was really about not making sure that every business got a little bit of money but trying to make sure that the awards were more targeted to businesses who really needed it,” Sheilley said. “And then we were able to provide more substantial grants to assist them, and I think that’s one of the really cool things that our, both from an elected official standpoint and from a county staff, that they understood and saw the need and the value in doing something different.”

Another $4.2 million went to help non-profits. The Community Foundation Ocala Marion County administered that money.

“I think some people have mentioned to me, ‘Well, you know, they should have gotten their applications in early,’” Lauren Deiorio, executive director for the foundation, said. “Well, the problem is we’re dealing with a nonprofit sector that lost almost all of their fundraising events, and a lot of them are left kind of scrambling so to speak to kind of figure out, you know, what they were going to do. Not necessarily month to month, but sometimes week to week. And so, to be able to stop – even though to me would make perfect sense to try to write some sort of a grant to get assistance – for some of them it was a little bit of a challenge.”

Deiorio said that there were nonprofits who planned on applying but couldn’t get it done in time.

“I do believe that there would have been more that would have applied if there had been more time,” she said. “Not necessarily at the level that we took in, you know, prior to that, but I do believe that there were some.”

But of the nonprofits that applied, Deiorio believes that the process served them well and kept them afloat.

“But I feel like after the fact, you know, the nonprofits were taken care of — that had applied,” she said. “I wish the process had stayed open a little bit longer, but, you know, they were being told by the state they needed to kind of wrap things up sooner than I think they anticipated.”

But the grants they did provide kept many non-profits afloat, she said.

The county’s share

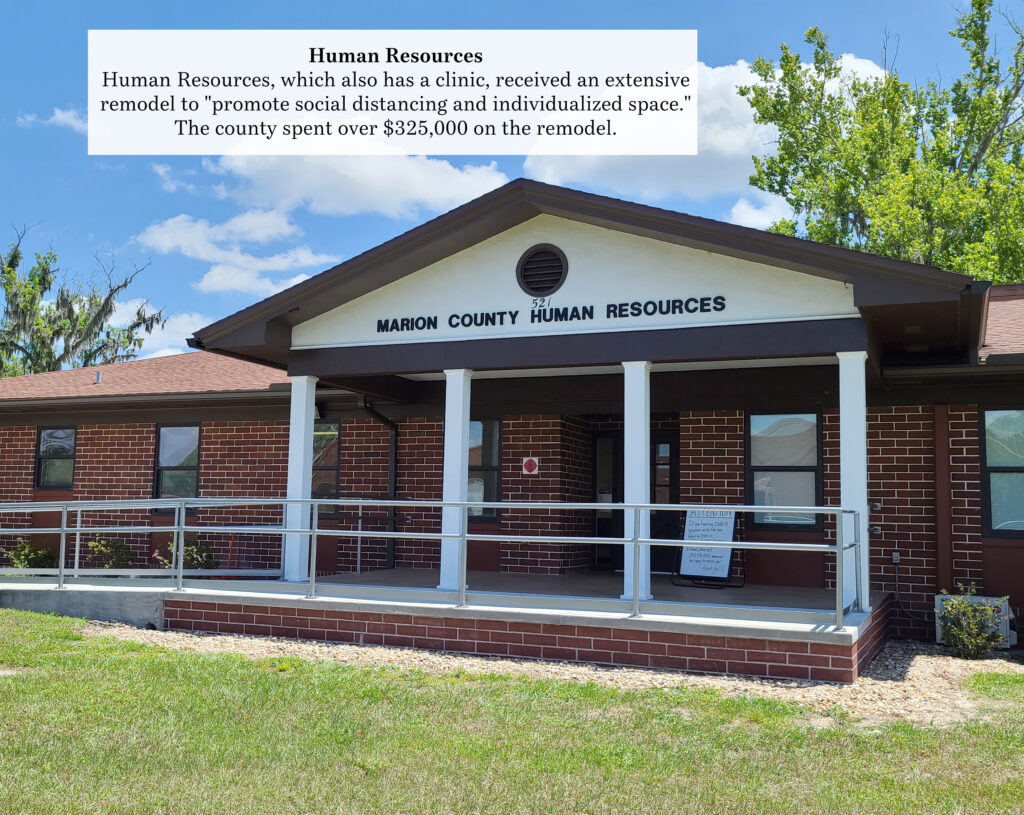

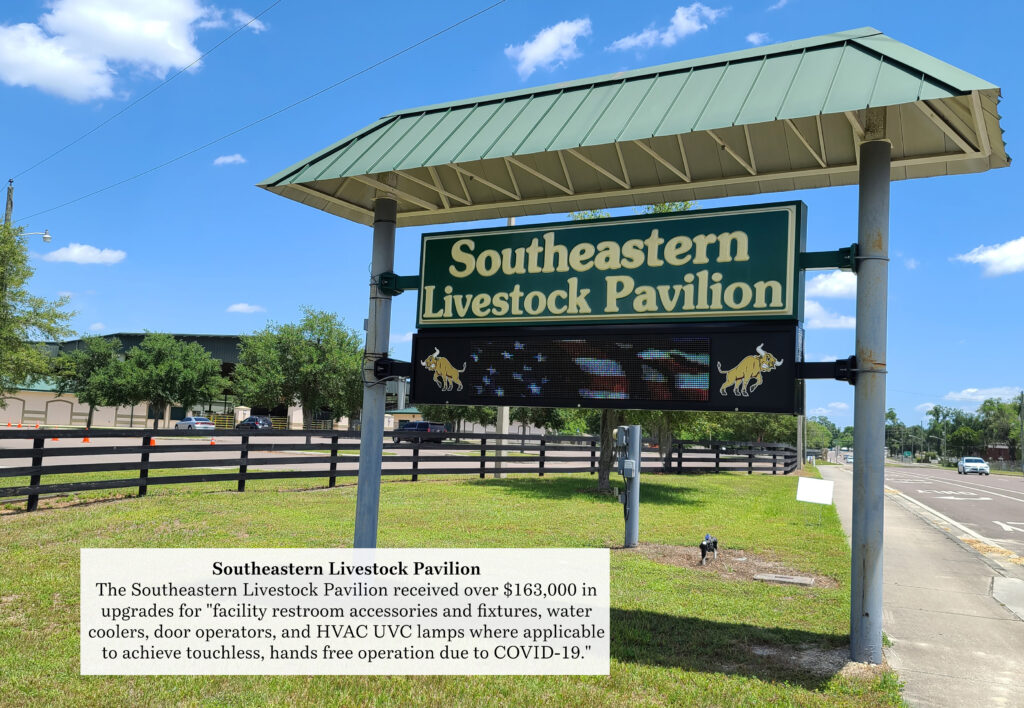

The county turned to two businesses to work on projects to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in county buildings: Johnson-Laux Construction and Ocala-based John Penn Construction.

Johnson-Laux Construction did much of the plumbing and air conditioning work for a total invoice of approximate $5.8 million. According to invoices, nearly $900,000 was spent on more than 200 touchless toilets, sinks, faucets and bottle fillers. Thousands more went toward ultraviolet lamps within the heating and air conditioning systems to kill viruses.

The projects were aimed to “achieve touchless, hands-free operation due to COVID-19.”

But on May 22, the Centers for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) issued a statement on how the virus spreads.

“The primary and most important mode of transmission for COVID-19 is through close contact from person-to-person,” the CDC said. “Based on data from lab studies on COVID-19 and what we know about similar respiratory diseases, it may be possible that a person can get COVID-19 by touching a surface or object that has the virus on it and then touching their own mouth, nose, or possibly their eyes, but this isn’t thought to be the main way the virus spreads.”

The county also spent about $350,000 to put new flooring in at fire stations across the county. Ocala-based John Penn Construction installed the floors among other projects.

The invoices for the work state the vinyl planking installed was to help “mitigate the spread of COVID-19 within the MCFR fire stations. The floors will help lessen the spread of COVID-19 and other airborne diseases.”

Gold defended the county’s spending, saying they worked to ensure that the county wasn’t spending money just to spend money.

“(I) was working during 9/11 and public safety, obviously. And I remember seeing the Homeland Security money coming out, it was just people were just spending it,” Gold said. “There was, I think, a case in Texas, I think they got like $1.7 billion in Homeland Security money and later on they found out they bought fish tanks all kind of, you know, things.

“They would say, ‘Oh, the fish tank is to train for swimming’ or something, but you know they were buying these things. And I just don’t see – and I don’t think the other commissioners see us just spending the money because we have it.”

Gold added that the county’s goal was to help its citizens during the pandemic while also saving money to prepare for future COVID-related expenses.

“If somebody came and asked me why we’re doing it this way or what it is, probably the best thing I’d say is that we want to make sure that the money is spent for what it’s intended to be spent on, and that is to help the citizens of Marion County recover and be prepared for any future COVID, you know, incidents that may happen or expenses that may happen,” he said.

But the county also spent nearly $600,000 to market itself during the pandemic.

Records show that the of the $600,000 paid to Paradise Advertising and Marketing of St. Petersburg, 93% of it was labeled as “other COVID-related expenditures.”

A total of $407,750 was spent on media buys, such as digital billboards, online advertisements and social media for a fall marketing campaign between October and December along with an additional $210,450 for production of photo shoots and video to advertise tourism in Marion County. The production was in the first week of December, and the marketing assets were delivered in the new year.

According to the minutes for the Tourism Development Council on Feb. 25, Jeannie Rickman, the assistant county administrator, said that the fall campaign was budgeted, but that CARES Act funding would replace it as part of the county’s recovery effort.

In an email to the Gazette, Rickman clarified herself, saying that the campaign would not have been possible without the funding.

“The CARES Act Funding was utilized to develop content and place media specific to COVID-19 recovery efforts,” she wrote. “Without the funding provided by the CARES Act, this campaign would not have existed. The ‘recovery’ campaign was over and above any budgeted amounts for the standard media planning campaign.”

Tourism Development’s budget has ballooned in recent years, increasing by 48% from the 2017-18 fiscal year to 2019-20, when it reached $3.18 million. The marketing budget for the 2020-21 fiscal year is unavailable because the county changed its system after 2019-20.

The Tourism Development’s marketing activities are usually funded by the bed tax, which is a tax charged to those staying in hotels. However, revenue generated by area hotels, motels and short-term rentals dropped more than 17.4% in 2020.

What the city’s got

DeSantis tasked the counties with providing “funds to municipalities located within their jurisdiction on a reimbursement basis for expenditures eligible under the CARES Act and related guidance.”

But in Marion County, the cities received about 2% of the $63.7 million.

Ocala received more than $750,000, Belleview got nearly $78,000 and Dunnellon has received more than $56,000.

Ashley Dobbs, Ocala spokeswoman, said the city has received only $21,000 for vaccination assistance from the county since November.

Donna Morse, Belleview’s deputy finance director, said the city requested an additional $19,000 in reimbursement but hasn’t received it yet.

Cities were only offered reimbursement for costs for personal protective equipment, testing, sick pay and vaccine costs.

Staci Winston, Chief Deputy of the Clerk of Court’s Office indicated on April 21st, “Our Finance team has advised the next report would be uploaded by the end of the month. We are hopeful to then post updated reports at the end of each month. Please feel free to check our website for these updates.”

The latest report was not available at press time. Check back for updates.

The last CRF accounting as of March 8, 2021 can be viewed using this link: CARES Act Status Report – 2021-03-08 (frontrunner-mccc.s3.amazonaws.com)