What happened to Fort Drane?

The old question is revisited after the Division of Historical Resources recently raised the issue in response to Marion County Board of County Commissioners’ request for changes to their comprehensive land plan to accommodate WEC developer’s plans for the old Ocala Jockey Club.

Fort Drane artifacts

The name Fort Drane easily rolls off the tongues of Lonnie K. Edwards III and Annabelle Leitner and it’s no wonder, the two often visited the Second Seminole War site near Irvine while growing up.

Edwards, now 80, didn’t have to travel far to see the ruins of the fort built in 1835 on the 3,000-acre Auld Lang Syne sugar plantation of Col. Duncan L. Clinch; it was located on thousands of acres of rolling bucolic pastureland his family had owned and farmed since the early 1900s.

“I remember the footings or foundations of not just one but multiple buildings there,” said Edwards, the oldest child of the late former State Senator L.K. Edwards Jr., a cattle rancher and farmer.

“We’d have birthday parties by fallen down oak trees on the property near the fort,” he said.

As for Leitner, her family knew the Edwards clan and they visited their nearby farm numerous times during her childhood, which included a visit to the site of the old fort on several occasions.

“Senator Edwards would pile all of us into his black stretch limo and drive across the pasture and up the hill to the fort and point out different things to us”, said Leitner, 63, who also went on several school field trips to the site in the 1960s. “I remember the cannon mounts and bricks; they were still there.”

The fort, erected on a hill near present-day two-lane West County Road 318 near the property line of the former Ocala Jockey Club, was abandoned by January of 1837 and was ultimately burned down, along with the plantation house, by Seminole warriors who then camped at the site for a short period of time.

But during its brief existence, Fort Drane was a busy hub of military activity. It housed thousands of soldiers, civilians and Native American refugees, served as a critical base for attacks against the Seminoles along the Withlacoochee River, and also functioned as a hospital for wounded and dying soldiers, according to historical records.

While state officials and historians had long debated Fort Drane’s exact location and place in the annals of Second Seminole War history, most everyone who grew up in rural northwest Marion County knew its storied history and its precise whereabouts.

“Everyone from around here knew where it was,” said Edwards, who said the family gatherings near the fort site often included stories about the fort and the old sugar mill plantation that had been passed down through the generations.

But now it’s gone

Today, however, if stunning allegations against the late owner of a local mining company and his son are true, it’s doubtful any remnants of the fort, as well as the remains of the dozens of American soldiers, Native Americans and civilians who were buried on its grounds, could be found.

According to a review by the Gazette of 50 pages of sworn statements taken in late August 1991, Mid-Florida Mining, then owned and operated by Whit Palmer Jr.

and managed by his son, Martin Palmer, allegedly destroyed any evidence of the fort as well as the human remains buried there.

The statements were taken on behalf of the now-defunct Friends of Fort Drane and the Marion County Historical Society and the still-in-existence Micanopy Historical Society, all of which had fought for years to prove the fort’s location in order to get the historically significant site recognized and preserved by local and state officials.

“They dug everything up and got rid of it,” said Jeffrey Winans of Reddick, who said he took pictures over the fence of the Ocala Jockey Club that allegedly show mine workers digging up the remainder of the fort in 1991. “All they cared about was mining the clay for kitty litter.”

Lonnie Edwards said he and the late Alyce Tincher, then president of the Micanopy Historical Society and a key leader in the long effort to save Fort Drane, had even approached Whit Palmer a year or so before the sworn statements were taken about the need to preserve and protect the site.

Tincher, who attended the same church as Palmer and considered him a friend, asked him to at least consider placing a historical marker at the mine, he said.

“We had an uproar with Whit about it; we tried to prevent it from being destroyed, but he didn’t care and didn’t want to hear about it,” said Edwards.

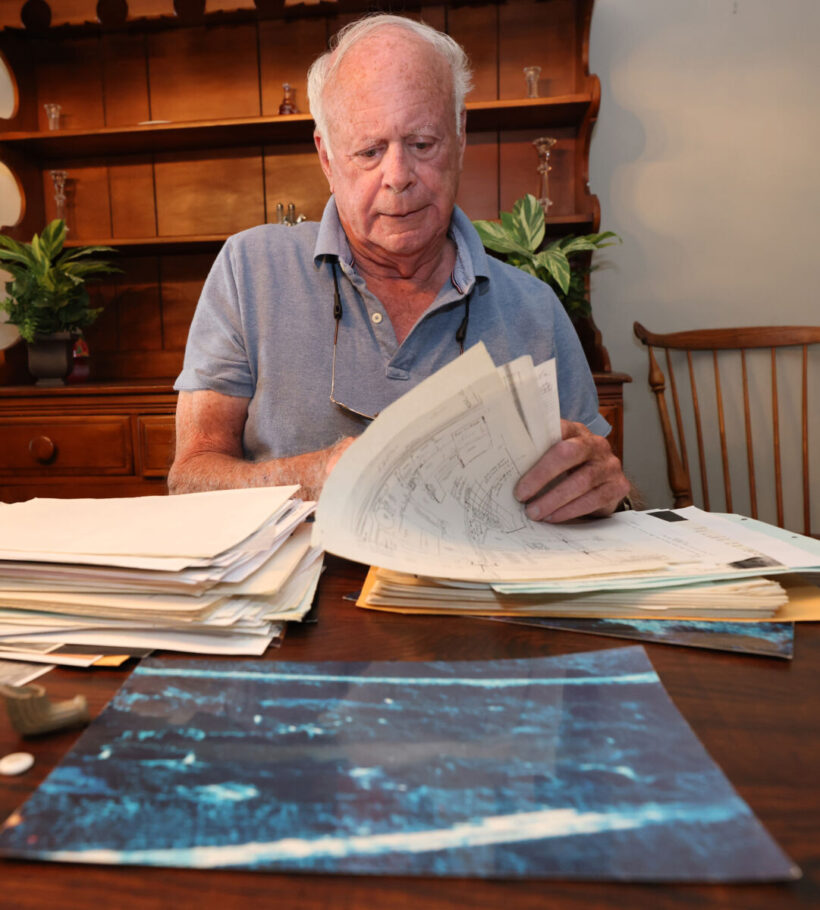

Jeffrey Winans looks through old paperwork and photos as he talks about the aerial photos he took of the Mid Florida Mining Site in 1991 at his home on Northwest County Road 329 north of Ocala on Thursday, May 19, 2022. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2022.

From Historic Fort to Mining Operation

In the early 1970s, Lonnie Edwards’ father sold a part of his property, including a large swath of the former sugar plantation, to M.J. Stavola Industries, which then sold it to Allen Edgar, founder of Mid-Florida Mining.

In 1977, Whit Palmer Jr. purchased Mid-Florida Mining and began mining the 700-plus-acre site for its clay soil, eventually becoming one of the nation’s top cat litter producers. Mid-Florida Mining, later MFM Industries, is now known as Palmer Resources, LLC., and leases the mine to SCI Materials, according to public records.

Whit Palmer Jr., a native of Ocala who died in 2020 at the age of 90, was well-known in the community for his many civic and charitable contributions, devotion to his alma mater, the University of Florida, and his influential business and political ties across the state.

Palmer’s daughter, Margaret Palmer Parks, speaking on behalf of the family and Palmer Resources, LLC, told the Gazette, “We cannot talk about the mine,’’ and declined any further comment.

But the sworn statements from former mine employees offer disturbing allegations of the deliberate destruction of the fort and the desecration of its graves: mine manager Martin Palmer, they stated, ordered human remains unearthed during mining operations to be reburied in a 50-foot-deep pit onsite.

Taken in late August 1991, the former employees, Dana Hughes and Thomas L. Reaves, both now deceased, gave grim accounts of finding remains that included human skulls with teeth and long bones in January that same year. Much, much larger bones, as big as a table, were also found, they said in their statements.

Winans, whose mother, the late noted horsewoman Carol Harris, employed the two men after they were fired shortly after the discovery and reburial of the human remains, said each of them spoke about what happened at the mine.

“Reaves told me they were told to keep quiet and keep on working because if the state found out about it, mining operations would stop,” said Winans. “Hughes was upset about the whole thing; they both were.”

The two men also said in their statements that artifacts and relics, including military buttons, broken swords, dishes, Native American pottery and arrowheads were dug up and removed altogether from the site by Martin Palmer and at least one of his friends.

Food lockers, lined, squared holes in the ground used to store food and provisions, were also dug up and destroyed, the men said.

The alleged desecration of the graves and the removal of the artifacts began roughly a month after Martin Palmer asked Hughes to stay late one day because he and a friend had found some bricks near an oak tree and he wanted Hughes to scrape the area.

“And I hung around there, and he (Martin Palmer) says, I think this is where Fort Drane – he mentioned Fort Drane, and I said Fort Drane ain’t back here, Fort Drane is up on the hill over there,” said Hughes, in his statement.

“So, he said, ‘come and show me,’” said Hughes, who stated he then took Martin Palmer and the friend to the site, where they found nails and military buttons, and other artifacts.

“But until that day, Martin Palmer didn’t know where Fort Drane was,” he said. Palmer had been mine manager for only a short period of time.

Hughes said two years earlier, two men who claimed they had permission to be on the property showed him the location of Fort Drane, saying they had been looking for it for seven years before finding it.

Around the same time Hughes showed Martin Palmer the fort site, the St. Petersburg Times, now the Tampa Bay Times learned about Fort Drane (and soon the efforts to save it) and sent a reporter to Mid-Florida Mining. The resulting story, Florida’s Lost Fort, ran on Dec. 2, 1990.

In the article, Martin Palmer mentioned the bricks he’d found near the base of the oak tree to a reporter, the same bricks he’d previously asked Hughes to scrape.

The company is asking an archaeologist to confirm the location, “just to kind of put the whole thing to rest,” Martin Palmer said in the story. Palmer also told the reporter, “The company does not want or need to mine in the area where soldiers and Seminoles once fought and died.”

Martin Palmer also said in the article, “We don’t want to ever disturb this fort.”

However, Whit Palmer was quoted in the same article as saying, “The problem is we don’t know where the mine is.” The quotes by the elder Palmer contradict Tincher and Edwards’ months-earlier conversation with him about the fort.

In January 1991, roughly a month after Hughes showed Martin Palmer the fort site and the Times article ran, Palmer ordered mining operations to begin in the area, which was pastureland, according to the statements.

The discovery of artifacts came first, but roughly a week later, about 40 feet or so away from the relics site, Hughes began digging up bones.

Hughes said in the statement that as soon as he saw a human skull with teeth in it, he told Palmer.

“Martin told me to, ‘Shut up and keep digging,’” said Hughes. Other employees also mentioned seeing bones to Palmer and the need for him to notify authorities, Hughes alleged.

“The operators – not only me but other operators in the mine — commented to him a few times about it, you know,” said Hughes in the sworn statement. “And he was very obnoxious about it, and just said, ‘If you don’t want to work here go somewhere else.’”

Human remains are protected under Florida law, which requires anyone finding them to immediately contact local law enforcement, which in turn contacts the local medical examiner who determines the age of the remains. If the remains are deemed to be 75-years-old or older, the case is turned over to the Florida Department of States, Division of Historical Resources, for investigation. It is not illegal for a private property owner to remove artifacts, however.

The sworn statements by Hughes and Reaves also include allegations that Mid-Florida Mining secretly buried contaminated soil on the site.

Nothing to see here

In the Spring of 1991, Gainesville-based archaeological firm SouthArc arrived at the mine to confirm Fort Drane’s location.

However, after five months SouthArc said it was unable to confirm its location on the basis of maps and historical information, according to an Aug. 1991 local newspaper column by the late David Cook. No digging was done in connection to the firm’s study, however.

But Joe Knetsch, Ph.D., a noted authority on the Seminole Indian Wars and retired research historian for the State of Florida, who was quoted in the Times article along with Tincher whom he had recently befriended over the Fort Drane saga, takes little stock in SouthArc’s 1991 findings.

“They were notorious in the field for finding what they were paid to find,” Knetsch told the Ocala Gazette. “And there was no digging.”

SouthArc was purchased by Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc., in July 2020, becoming part of its network of archaeological firms. A woman who answered the phone at Commonwealth’s Gainesville office said Martin Dickinson, the founder of SouthArc who conducted the 1991 mine survey, retired and was no longer available.

The frontier fort, a 150 yard by 80-yard picketed fence enclosure with two blockhouses and several other buildings, may have had a brief existence, but some famous military leaders passed through its gates, Knetsch told the Gazette.

“Benjamin Pierce, the brother of the eventual President (Franklin Pierce), Lt. Col. Ichabod Crane and Col. Zachary Taylor who became President, were all there at one time or another,” he said, “Three thousand soldiers passed through Fort Drane; it was the Army’s largest outpost at one time.”

“There’s no way in hell there weren’t artifacts and remains left behind,” he said.

Knetsch said Tincher sent officials at the Florida Department of State a package of information about Fort Drane, including the sworn statements about the desecrations. He and other employees, including state archeologist Henry Baker, began investigating but were soon ordered to stop.

“It was political; it was shut down at the state level from the top on down,” said Knetsch, author of several books including Florida’s Seminole Wars 1817-1858 and Fear and Anxiety on the Florida Frontier, which includes a story about Fort Drane. The Times, according to Knetsch, began working on the story after he gave a speech about the fort in Ocala.

“Whenever we tried to get something done, we were stonewalled,” he said. “Henry (Baker) had gotten some aerial photos at some point, which he believed showed some discoloration on the ground that was orderly in nature and would indicate burial plots.”

“But his file on Fort Drane disappeared from his desk and he never found it again,” said Knetsch.

Winans, who was involved in the effort to save Fort Drane, and wrote a book, What Happened to Fort Drane in Marion County, based on his research, said by the time SouthArc surveyed the site it was too late; its ruins had been destroyed and its graves desecrated.

In the sworn statements, Martin Palmer was also quoted as saying, “If there ain’t nothing there, then nothing will be found.”

Timothy Parsons, director of the Department of State’s Historical Resources division, has not responded to requests from the Gazette to discuss questions about Fort Drane. Morgan Mallory, spokeswoman for the Department of State, sent an email offering her assistance for this story but has not responded to subsequent messages from the Gazette.

Renewed interest

However, the Division of Historical Resources, along with other state agencies, did review a recent request by Marion County to make changes to its comprehensive land use plan that would allow major development on the former Ocala Jockey Club property, which was purchased last year and is now known as the World Equestrian Center (WEC) Jockey Club.

In a letter dated April 20, the Division of Historical Resources did note the numerous cultural resources recorded in the general vicinity of the property and that there had been multiple attempts to locate a potential historic site known as Fort Drane, which is thought to contain human remains, in the immediate area.

The agency also noted a cultural resource assessment survey had not been conducted to determine if unrecorded historic resources are present and said development should be “sensitive,” to locating, assessing, and avoiding potential adverse impacts to any resources.

In their sworn statements, Hughes and Reaves both mention Fort Drane as being located very near the property line of the Ocala Jockey Club, a good portion of which had been part of the massive Auld Lang Syne plantation at one time.

The response by the Division of Historical Resources is what prompted the Ocala Gazette investigation into what happened to Fort Drane, which led to the discovery of the sworn statements.

Local conservation and environmental groups, including Save Our Rural Lands (SORA) have voiced strong opposition to the PUD application by the developer of the WEC Jockey Club, which is within the county’s Farmland Preservation Area and outside its Urban Growth Boundary.

“History doesn’t stop at a fence line,” said Gail Stern of SORA. “There needs to be a cultural resources survey done to determine who and what is buried on the property.”

In 1991, the historical groups, led by Tincher, reportedly also contacted local officials about, “a crime being committed,” but both Glen Fiorello and Gail Cross, who served on the Marion County Commission during that time, said they do not recall hearing anything about Fort Drane.

A search of Marion County’s Clerk of Court website about Fort Drane came up empty, except for several columns by Cook. The Marion County Sheriff’s Office also said it had not received a complaint about Fort Drane, but did receive one on a reported African American slave cemetery on the mine property.

An email to the American Indian Movement, Florida chapter, as well as the Florida Historical Society, requesting comment on the allegations had not been answered as of press time.

Knetsch said he has no doubt the accusations against Mid-Florida Mining are true.

“Those men had everything to lose and nothing to gain by coming forward,” he said. “Other people were there and said the same thing.”

“Alyce worked her fanny off trying to save Fort Drane,” said Knetsch. “What happened still bothers me after all these years.”

For Edwards and Leitner and other residents who were born and raised in the rural enclave, the proposed development at the former Ocala Jockey Club brings back memories of Fort Drane and the Auld Lang Syne sugar plantation.

“We all knew where it was,” said Leitner, who still lives on farmland her family settled on in 1842 not too far from the mine. “It was on top of the hill at the kitty litter mine.”

“Maybe now the truth will come out,” she said.