Sheriff proposes absorbing school district’s safe school department

The move would shift management of this department from the superintendent to the sheriff.

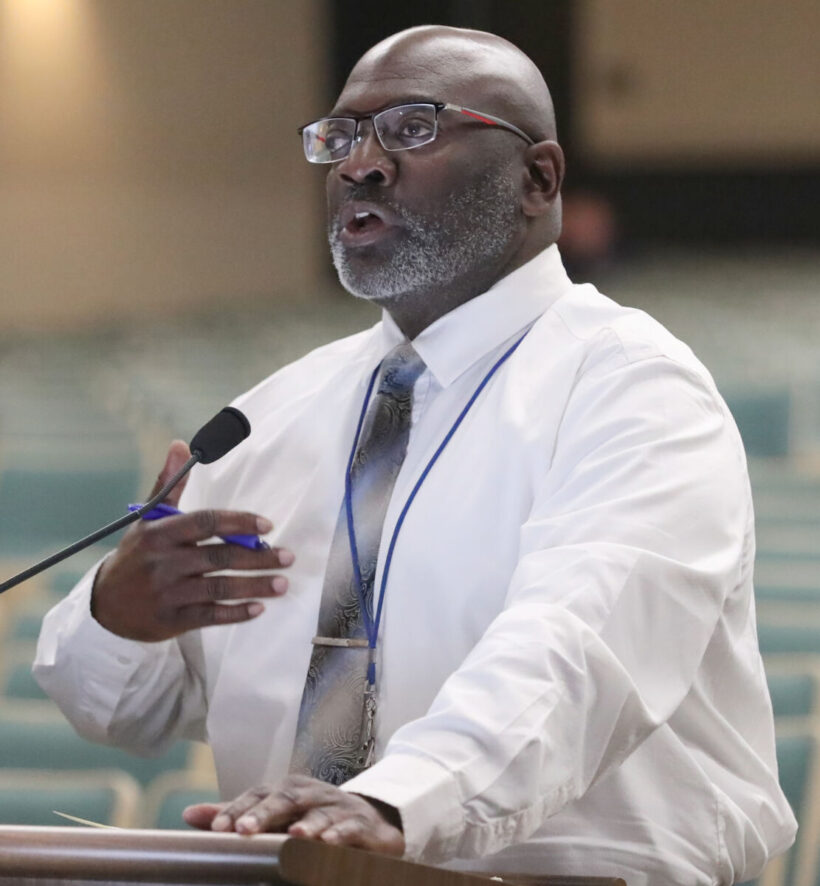

Marion County Sheriff Billy Woods speaks during the Marion County School Board workshop in Ocala on Thursday, Oct. 20, 2022. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2022.

The Marion County School Board during its Oct. 20 work session discussed a proposal from Sheriff Billy Woods to absorb the district’s safe school department that now falls under the authority of the school superintendent.

The superintendent told the board the discussion was only meant to glean initial impressions of the board to the proposal before gathering more information and feedback from schools about the possible implications of the move.

Security is a major concern for the school district which, with a population of more than 50,000 students and faculty on any given Monday through Friday, is comparable to that of a small city. The workshop conversation gave some insight into some of the nuances the district must navigate when it comes to “policing” minors.

According to the school district, the safe school department handles things such as “emergency drills and exercises at all schools, security enforcement and enhancement on all school district property (including School Board meetings and work sessions), security equipment including fencing, cameras, and entry access.” Additionally, “the department contributes to student programs including bullying prevention, fostering direct communications with school administrators regarding security concerns, responding to emergencies, alarms, threats of violence, and other safety concerns on any school property.”

As to handling discipline matters, the district indicated that the safe schools has input, but the actual processing of suspensions or expulsions are handled by area superintendents.

The attorney for the district, Jeremy Powers, told the board that Florida statutes were broad on the district’s choices for staffing school safety: the use of school resource officers, private security, the guardian program, even creating the district’s own internal police department.

The district, he explained, has adopted a plan that relies 95% on school resource officers staffed by the sheriff’s office, the Ocala Police Department and the Belleview Police Department. These contracts for school safety cost the district more than $13 million annually.

The district also has a Department of Safe Schools led by Dennis McFatten.

The Gazette’s review of McFatten’s employment file reflects his more than two decades of experience working for Marion County Sheriff’s office as a patrol captain. Before that, he worked four and half years as a corrections officer, and he served six years in the U.S. Army as a military police officer.

McFatten’s employment file contained no negative comments from school officials.

McFatten began working for the district in 2017 following an unsuccessful bid to be elected Marion County sheriff in 2016. More than 63,000 people voted for McFatten in that race, but Woods received 62% of the vote.

Under the sheriff’s proposal, McFatten, as well as four other school safety department employees, would become employees of the sheriff’s office and would report to the captain of the sheriff’s Juvenile Division.

The annual cost of personnel for the safe school department, including salary and benefits, is approximately $450,000. The sheriff indicated the move would not create additional expense for the district.

“I am just asking you to pay 100% of what it currently costs you for those employees within your annual budget,” the sheriff explained in a letter to Superintendent Diane Gulliet.

“Simply put, I will take these employees … and they will continue to perform the same duties and responsibilities that you have outlined within your job descriptions for their positions,’’ the letter continued. “They will be fully sworn deputy sheriffs and will be able to provide law enforcement capability security with full arrest powers at your School Board meetings and any other function that you deem necessary. The one Safety Specialist that has a Correctional Certificate I will send and pay for his cross-over training and certificate.”

Dennis McFatten, the School District’s Safe Schools coordinator, speaks during the Marion County School Board workshop in Ocala on Thursday, Oct. 20, 2022. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2022.

“With all due respect to the sheriff and the chiefs,’’ he said, “I don’t feel comfortable in that proposal for where it leaves me and my staff or the school district and our kids.”

McFatten expressed confidence in the resource officers placed in schools, but he told the board that their role was different than the school safety department’s role, which focuses more on preventive measures.

“We are more than the fences, door buzzers and cameras of this district,” he said.

Speaking about the worst nightmare for school officials and the community, an active shooter in a school, McFatten tried to put the fears into perspective.

“There is a small likelihood that a school shooting will occur,’’ he said. “Can it happen? Absolutely, on any given day. However, what does happen on a daily basis with your safe school department…is what we are talking about here today.”

School board members Kelly King and Don Browning both expressed support for the sheriff’s proposal.

King said shifting that department from the superintendent’s purview to the sheriff’s would allow the superintendent to concentrate more on academics and leave safety to the “experts.”

Board member Eric Cummings pointed out that McFatten was also an “expert,” to which King quickly agreed and expressed admiration for the work of McFatten’s department.

King raised a question to the school district attorney how they would navigate protecting information about school district records that is currently exempt from sharing with law enforcement. Powers agreed that issue would need to be explored and protections incorporated into the contract.

Board member Nancy Thrower said she was speaking from the perspective of a longtime educator “in the trenches.” She said, “In a school setting, education and school safety are not mutually exclusive,” and that was why “trust and communication” were necessary.

Thrower, along with the other board members, expressed confidence and appreciation for the sheriff’s efforts to protect students. However, Thrower pointed out that the cordial supportive relationship that exists between the agencies could change with leaders being replaced during election cycles.

School Board Vice-Chair Allison Campbell asked how the school’s code of conduct and disciplinary measures would be factored in when, for example, students got into a fight at school. The sheriff said that in those cases, an arrest would be made because a fight is considered a battery and the law requires it.

When the Gazette asked for clarification after the meeting about the sheriff’s stance on arresting students following a fight, sheriff’s attorney Timothy McCourt said an “officer always has the authority to make an arrest, regardless of who is managing Safe Schools, and that no School Board policy can override a law enforcement officer’s duty to enforce Florida law.’’

“But just because an arrest can be made doesn’t mean an arrest should be made,’’ he said. “The sheriff believes that oftentimes discipline of children for things like fighting or disorderly conduct is best handled by the kids’ parents and by their schools.”

Campbell raised other issues in the proposal that gave her pause. She questioned the impact the arrangement might have on the support the district has enjoyed from McFatten’s team. She noted the school safety department employees, despite all having law enforcement backgrounds, chose to work for the district rather than one of the area’s law enforcement agencies.

Campbell also wondered whether the district would lose those employees in the transition. She likened it to the personnel loss that sometimes results from a corporate merger when some employees leave because of a potential shift in company culture.

Numerous times during the discussion, the chain of command during an active shooter situation was raised. McFatten told the board that there has never been a question of chain of command during an active shooter situation: the law enforcement agency responding to the threat is in charge.

Pointing to the 24/7 access McFatten gave to the school district, answering calls at all hours of the night, the trust between himself and school principals and department heads, McFatten explained that school safety involves more than just active shooters, it was also about “discipline, threat assessments and mental health.”

The sheriff assured the board that they would receive the same continuity care from the school safety department under his leadership. He also agreed to amend the contract to address some of their concerns about accessibility to records and providing a 24/7 security hotline.

McFatten expressed disappointment that the sheriff and police chiefs had worked on this proposal for at least six months without approaching him or explaining why they felt this change was necessary, despite McFatten’s request for communication.

McFatten also told the board that his department felt disrespected and the invitation to join the sheriff’s “family” seemed disingenuous since they were referred to as “kindergarten cops and a Mickey Mouse operation.”

In the Gazette’s follow up with the sheriff’s office, McCourt said McFatten’s comments about being disrespected are unfounded. He added that the sheriff and police chiefs were only following the chain of command by going to the superintendent rather than McFatten as she oversees the safe school department.

McCourt also dismissed that notion that the sheriff would discuss the matter with McFatten at all, even if there were operational concerns. Operational issues, he said, would be handled on a case-by-case basis by the sheriff’s Juvenile Division supervisors.

“If issues rose to the level where the sheriff needed to personally intervene, he would address them with the superintendent or members of school board,” McCourt said.

Cummings questioned the need to make any changes since the current plan was working. He also recalled advice of fellow board member Browning “not to give away authority because its hard to get it back.”

At least seven members of the public spoke to the board during the meeting raising concerns about what increased policing could have on youth. Most encouraged the board to consider that school safety was more than just about “getting the bad guy.”

The superintendent told the board she would come back with answers to the board’s questions, feedback from the schools, and department employees who would be impacted by the change.