Local advocates for lung cancer patients encourage broader use of a vital screening tool

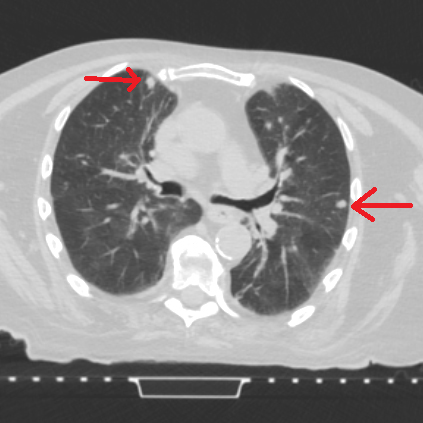

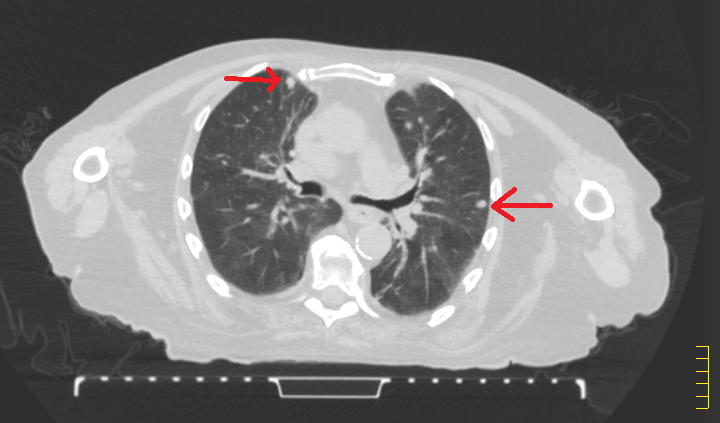

Photo courtesy of Brad Beck, medial physicist with the Robert Boissoneault Oncology Institute in Ocala. This photo shows a low-dose computed tomography image of lungs of a patient at the Robert Boissoneault Oncology Institute. The highlighted areas show spots of concern for potential lung cancer. LDCT is able to see such areas significantly earlier than traditional chest X-rays.

Cancer is a silent killer, and lung cancer is more lethal than most forms of the disease.

Lung cancer kills more Americans each year than breast, colon, prostate and brain cancer combined, medical authorities say. And more than half of its victims die within a year of being diagnosed, according to the American Lung Association.

Meanwhile, fewer than one in five lung cancer patients make it to the critical five-year survival mark — which, comparatively, is achieved by nearly two-thirds of colon cancer victims, nine of 10 breast cancer patients and 98 percent of those diagnosed with prostate cancer.

That’s because most lung cancer victims never realize they are ill until it’s too late.

But advocates for lung cancer patients in Marion County – where rates of both lung cancer diagnoses and deaths outpace those statewide — are seeking to improve their odds.

They’re doing so by calling attention to a screening tool that is more effective than chest X-rays at catching tiny cancer cells in the lungs, but which they say gets too little use

It’s called low-dose computed tomography, or LDCT.

“It’s a much better screening tool, but it’s not really being considered as much or as much as it could be,” said Amy Roberts, chairwoman of the Cancer Alliance of Marion County, and a licensed clinical social worker with the Robert Boissoneault Oncology Institute in Ocala.

In fact, on its website the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that LDCT is the “only recommended screening test for lung cancer.”

Still, Roberts said, a knowledge gap exists locally about utilizing LDCT more broadly.

Consequently, her group and both of Ocala’s hospitals seek to promote the life-saving potential of LDCT among the public and the medical community.

LDCT is a version of the traditional CT scan. It takes just a few minutes and greatly reduces the patient’s radiation exposure. The procedure uses about one-tenth of the radiation of the regular CT scan, according to lung cancer specialists at both Ocala Regional Medical Center and Advent Health Ocala.

Roberts suggested one reason LDCT is not more broadly used is that it only recently became eligible for coverage by Medicare and many private insurers.

The U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or CMS, did not implement Medicare coverage for LDCT until January 2016.

In a report about its decision, the CMS noted that the government spent years looking for a “suitable” screening test for lung cancer.

The earliest methods, dating to the 1960’s and ’70’s, were chest X-rays and testing a patient’s mucus for cancer cells. Both “failed to conclusively demonstrate improvements in health outcomes,” the CMS report noted.

LDCT first appeared on the government’s radar in the 1990s. While federal officials acknowledged its potential, the government, even by the early 2000s, found insufficient evidence to use LDCT to routinely screen asymptomatic people for lung cancer, the report said.

That did not change until 2011. That year, the National Cancer Institute published a study that indicated heavy smokers between 55 and 74 were 20 percent less likely to die from lung cancer if they received an LDCT screen. Meanwhile, the CMS report observed, “Previous studies had shown that screening with standard chest x-rays does not reduce the mortality rate from lung cancer.”

Three years later, the government was convinced of LDCT’s benefits and released updated screening recommendations. Those included using LDCT annually for people between 55 and 80 who are current smokers or have quit within the last 15 years, and who have a history of heavy smoking, defined as a “30-pack-year” habit, meaning the equivalent of smoking a pack a day for a year over 30 years.

The procedure is more expensive, running about $200 compared to just $80 for a traditional X-ray, said Lisa McGuire, lung nodule coordinator for Ocala Regional Medical Center and West Marion Community Hospital.

Yet the difference in imaging results is dramatic.

Whereas an X-ray provides a view of the lungs from the front and side and captures everything in the chest cavity, LDCT returns hundreds of images specifically portraying very thinly sliced cuts of those organs.

Such precise, focused imaging, McGuire said, allows doctors to see tumors far sooner than with a traditional X-ray.

According to the website VeryWellHealth.com, the LDCT procedure can spot a lung tumor as small as 4 millimeters. By comparison, an X-ray can miss those smaller than 1.5 centimeters.

In other words, in many, if not most, cases an X-ray would not detect a lung tumor until it grew four times as large as what the LDCT can pick up.

Here’s why that’s critical.

The American Lung Association notes that 56 percent of patients survive at least five years when the cancer is discovered while still in the lung. But only 16 percent of patients are diagnosed that early.

Comparatively, if the cancer escapes to other parts of the body, as happens when it reaches stages III or IV, the five-year survival rate plummets to 5 percent.

“This test is not being ordered enough,” McGuire said.

“I really think we need to shift the paradigm so that those doctors order this screening like they do a mammogram or a colonoscopy, particularly with our demographics and an older population with a history of smoking.”

Even without broader use of the LDCT test, lung cancer rates in Marion County are falling.

The Florida Department of Health reported a recent peak of 91 cases per 100,000 county residents in 2005. As of 2017, the latest year data is available, that had fallen to 66 per 100,000.

Deaths are declining, too. Over that same time frame, the mortality rate dropped from 68 per 100,000 to 40.

Roberts, of the Cancer Alliance, attributed that to aggressive anti-smoking campaigns, especially those targeting children and young adults, and better therapeutic drugs.

But, said Janelle Hom, executive director of the American Lung Association in Florida, “Screening for individuals at high risk has the potential to dramatically improve lung cancer survival rates by finding the disease at an earlier stage when it is more likely to be curable.”

“Early detection, by low-dose CT screening, can decrease lung cancer mortality by 14 to 20 percent among high-risk populations,” she continued. “In fact, about 8 million Americans qualify as high risk for lung cancer and are recommended to receive annual screening with low-dose CT scans. If half of these high-risk individuals were screened, over 12,000 lung cancer deaths could be prevented.”

Laura Eatmon, the lung health nurse navigator at Advent Health, said she is passionate about this because earlier detection might have saved her grandfather from dying from lung cancer.

Eatmon said many people at risk of lung cancer struggle with a “shame factor” that makes them reluctant to disclose their smoking habit, even with a doctor.

“They’re scared, and there is no reason for them to be,” she said. “Lung cancer prevention, lung cancer screening and lung cancer awareness are near and dear to our hearts. We want people to get screened — and save their lives.”

McGuire notes that LDCT didn’t become a mainstream screening technique until around 2010, and many who may have benefitted shied away because it was not covered by insurance.

At the time, just 3.3 percent of those meeting the risk criteria across the country received the test, she said. Yet after five years, that had risen to only 3.9 percent. That translates to screening just 265,000 of the 6.8 million people eligible at the time.

Roberts, of the Cancer Alliance, said early detection must be stressed since so many people don’t learn they are ill in time – often finding out when being examined for something else.

“We all want to help with prevention,” Roberts said. Finding out too late, she added, means “it’s a lot more challenging for the patient and the family. Their mortality is higher and their quality of life is lower.”