Federal rental relief distributed quickly, but not without challenges

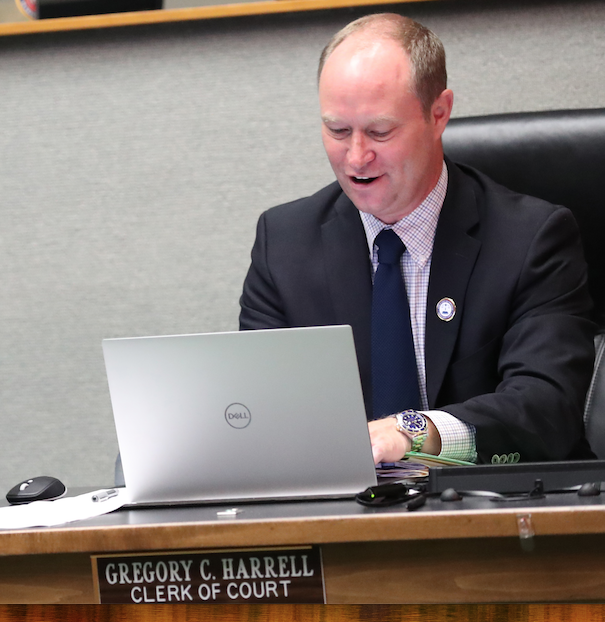

In this file photo, Clerk of Court Greg Harrell sits during the Marion County Commission meeting at the McPherson Governmental Complex in Ocala, Fla. on Tuesday, Nov. 2, 2021. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2021.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated with new information.

Tasked with moving over $11 million in federal rental assistance funds to residents impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic last year in less than seven months, Marion County officials faced a daunting challenge. No mechanism existed to allocate the money, and the clock was ticking.

The first round of Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA1) funding was intended to help those who had lost income, incurred significant costs or other financial hardships due to COVID-19. To hasten the distribution process, the county turned to United Way of Marion County to help manage the outreach into the community.

While the effort officially began in January 2021 when Marion County signed off on an agreement with the U.S. Treasury Department, the county did not start rolling out the money until it entered into a separate agreement with the United Way in April 2021.

According to that agreement, the United Way had till July 31, 2021, or a little more than three months, to distribute the funds, which ultimately amounted to $11,038,909.

To speed things up, county officials connected United Way with Capital Access (CA), a company that has worked with Marion County on similar projects. United Way and CA became “subrecipients” of the grant funds and answered directly to the county commission who, in turn, answered to the U.S. Treasury, the source of the funds.

Using a newly devised system to distribute millions of dollars in emergency aid to residents and businesses in a compressed time period during a pandemic was a recipe for missteps. Since neither the county administration nor the county Finance Department would be directly monitoring ERA1 activity, county officials knew they needed some oversight to provide accountability to the Treasury for the funds.

County leadership determined that Sachiko Horikawa, the county’s internal audit director for the county at the Clerk of Court’s office, would ensure the parties complied with the agreements.

In a subsequent audit, Horikawa’s team identified a number of problems, many of which were corrected soon after they raised them. The report, however, was also noteworthy for what was not included: possible conflicts involving county officials involved with the relief effort.

For this article, the internal auditor, Horikawa, and Clerk of Court, Gregory Harrell, would not grant the “Gazette” request for a telephone interview about the audit report and would only answer questions in writing by email through the clerk of court’s public information officer.

Funding challenges

Facing a looming deadline, the United Way and CA had to invent a system for distributing the money. They created an online portal where both landlords and tenants seeking grants would provide supporting documentation and written and verbal attestations. CA reviewed payee information and identified duplication of benefits and any other concerns.

If approved, the applicant’s name, payee information and amount due were sent to United Way. Payments were made directly to the payee (landlord or utility company), though there was an option to pay the applicant directly if the payee was uncooperative.

Horikawa’s team tested a sample size of 40 randomly chosen approved and funded applicants, landlords and utility companies.

They flagged several issues, including documentation for the applications and conflicts with information already in the HMIS system, a database used across many agencies to ensure that people don’t receive duplication of benefits.

Of the 40 applications, the auditors wrote: “UW did not include a birthdate for 23 applicants. The remaining 17 had correct birthdates added previously by other agencies.” Also, “All 40 applicants had incorrect income information and half those applicants had incorrect household size.”

The auditor also noted that United Way was paying utilities. While the Treasury allowed this, the county’s subcontract with United Way did not.

After the review, Horikawa reached out to the county, United Way and CA to tighten up the process. Horikawa agreed to not issue an audit report until United Way and CA had been given time to make the adjustments.

On April 27 of this year, Horikawa released the audit to the Marion County Board of County Commissioners and County Administrator Mounir Bouyounes.

Here are some of the issues and remedies identified in the report:

- Two employees of the United Way received rent payments of $4,350 and $3,680 respectively after applying as tenants, even though the county’s agreement with the agency prohibited United Way and CA employees from receiving ERA1 fund. Officials intercepted a payment to a third employee before it could be made. The United Way returned the money to the county.

- The auditor was concerned that ERA1 funds were “comingled” in the same United Way account that held Coronavirus Relief Funds (CRF). United Way provided documentation showing the account had essentially been emptied of CRF before ERA1 funds were deposited.

- CA did not have all of the required documentation related to applicants’ grant eligibility and they weren’t crosschecking HMIS. When used appropriately, HMIS mitigates the risk of duplicate funding by allowing CA to verify if other funding was awarded prior to approval of funding, and for UW to document funding provided to assist other agencies when performing duplicate benefit searches. CA did not consistently follow up with discrepancies or questionable supporting documentation, relying on “self-attestation.” The auditor noted the county’s agreement with United Way and CA did not specify when attestation should be relied on over supporting documentation.

- CA Projects and Grant Management Services (CAPGMS) portal lacked adequate internal controls compromising the integrity and availability of the data because too many people had access to change or update information without keeping track of who was making the changes or what the changes were Once this risk was identified, CA did tighten up access to what information could be edited in the system.

- CA allowed payments for prospective utilities when the county agreement prohibited such payments. The county amended its agreement retroactively with the UW and CA to allow for utility payments in line with the Treasury’s guidelines. “We are aware that the Treasury rules allowed a longer period of prospective payments on utility than the county allowed. County limited it to up to three months,” said Horikawa. “The Treasury rules also allowed for assistance for the internet.”

- CA case managers and quality control managers did not accurately determine household income for some applicants or provide the correct amounts for eligible funding.

Issues not addressed in the auditor’s report

Although not mentioned in the auditor’s report, a Gazette public records review indicates that Marion County Commissioner Kathy Bryant-House received $4,700 in ERA1 funds. Bryant-House is a licensed Realtor and a landlord.

When asked why there is no conflict for county commissioners, who are ultimately responsible for overseeing the ERA1 funds, in receiving these funds, Horikawa told the Gazette: “I am not aware of any Treasury rules that would preclude Commissioner Bryant from receiving ERA1 funds as a landlord.”

But there also is no Treasury rule forbidding United Way or CA employees from receiving ERA1 grant money. That condition was added by the commissioners to their agreement with UW and CA.

At a commission meeting last summer, Bryant-House recused herself from voting on any ERA-related business to avoid any conflicts of interest.

The “Gazette” emailed the county spokesperson asking the county to explain why their agreement conflicted UW employees from receiving ERA1 funds but not commissioners.

The county responded by saying: “The emergency rental assistance applied for by a tenant of Commissioner Kathy Bryant was provided in accordance with U.S. Treasury guidelines as well as the county’s contract with the funding administrator, the United Way of Marion County. The county’s contract specifies that the funding administrator nor its employees are permitted to also receive the funds they administer.”

The audit also makes no mention of potential conflicts of interest involving Clerk of Court and Comptroller Gregory Harrell, whose office oversees Horikawa and her team, and his involvement with one of the parties under review. Harrell was on the United Way board of directors and became chair of the organization on Aug. 25, 2021.

Here is how Horikawa explained the relationship.

“In this audit, as well as other audits, Clerk Harrell did not/does not direct how the audit should be performed or ask to change our findings. He has an opportunity to review our draft reports for readability and attend the exit conference,” she said.

“It is important to note that our objective and scope were to ensure that payments made were within the boundary of the Treasury guidelines and the county agreement,” Horikawa added. “It was not our scope to identify all the differences between the Treasury guidelines and the county agreement as the county was allowed to establish its own rules as a grantee so long as it did not violate the Treasury guidelines.”

Harrell told the “Gazette” that he recused himself from both the audit and financial functions associated with the county’s ERA1 program and did not have any management-level decision-making role into how the funds would be spent.

Harrell said he told Horikawa and General Counsel Rob Davis at the audit’s outset that, while the final report for the audit would be published to the Board of County Commissioners and County Management on Clerk letterhead because, under Article VIII, Section 1(d) of the Florida Constitution, a clerk of the circuit court is the auditor of all county funds, he would be recusing himself from that role in this instance as much as possible and delegating it to Horikawa and her team.

“While I did not supervise, restrict or alter the auditing team’s substantive work on this audit, I did review report drafts to suggest grammatical changes for ease of reading,’’ Harrell said. “However, I did not change, or suggest to change, any finding contained within the reports.”

Harrell also recused himself from ERA1 matters at the United Way’s board meeting on July 28, 2021.

“The Internal Audit Director independently performed the ERA1 audit and the Finance Director independently coordinated the receipt and disbursement of ERA funds,” Harrell said on May 19. “As the Board Chair of United Way, I did not vote, or, in any way, influence the decisions associated with the ERA program.”

“As the Clerk of Court and Comptroller,” he continued, “my ability to perform my statutory and constitutional responsibilities with independence and professional objectivity were never compromised.”

Last Tuesday, the auditor’s report was attached to the agenda for the county commission’s May 17 regular meeting; however, the report was not brought up for discussion.

In this file photo, Scot Quintel, the president of the United Way of Marion County, poses for a photo at the United Way in Ocala, Fla. on Monday, Nov. 9, 2020. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2020.

United Way’s challenge

In response to the auditor’s concerns, United Way’s Executive Director Scot Quintel issued a memorandum on Aug. 19, 2021, which as included in the auditor’s report, stating that in order for CA to succeed “at the scale and time frame as specified” by the agreement the county made with the Treasury, it needed its CAP (COVID-19 Assistance Program) team to be held accountable to the ERA1 rules stipulated by Treasury and not be “overburdened” with state and county rules that seemed to muddy up the process.

According to Quintel, in an email from the White House Intergovernmental Affairs office dated Aug. 18, 2021, the day before his memo, the administration stressed, “ERA programs can and should use simple forms and remove unnecessary documentation requirements to move swiftly to distribute ERA funds.”

“They [could] do so without falling out of compliance with the program regulation,” said Quintel on May 18. “The context in that [above mentioned] memo [from the auditor’s report on Aug. 19] was to remind all partners of the guidance provided by U.S. Treasury administration.”

Horikawa advised that county administration continue to monitor the subrecipient for the next ERA program—ERA2—that started “recapturing and reallocating” funds on March 31, 2022, according to the Treasury’s website.

The auditor further advised future vigilance to ensure the amount of direct assistance disbursed is compliant with Treasury rules.

Marion County was allocated $8.7 million in its next wave of federal rental relief, according to Marion County Senior Public Relations Specialist Stacie Causey, which it has been receiving in roughly $3 million chunks since last year.

As of May 24, the county is awaiting receipt of the final $2.6 million in ERA2 funds, said Causey, adding she had no guarantee yet of when that money would be received from the U.S. Treasury.

At this point, the county has received upwards of 75% of the ERA2 funds or approximately $6.1 million. UW has a Sept. 30, 2025 deadline to distribute all allocated ERA2 funds.