Trinity Catholic pays off mortgage after 20 years

Blessed Trinity Catholic School in Ocala was founded in 1927, and for decades afterward, parents had three options to continue their children’s education after they completed the eighth grade: attend a local public high school, travel nearly 100 miles to enroll in a Catholic high school or, for a brief period, finish at St. John Lutheran School in Ocala.

Blessed Trinity Catholic School in Ocala was founded in 1927, and for decades afterward, parents had three options to continue their children’s education after they completed the eighth grade: attend a local public high school, travel nearly 100 miles to enroll in a Catholic high school or, for a brief period, finish at St. John Lutheran School in Ocala.

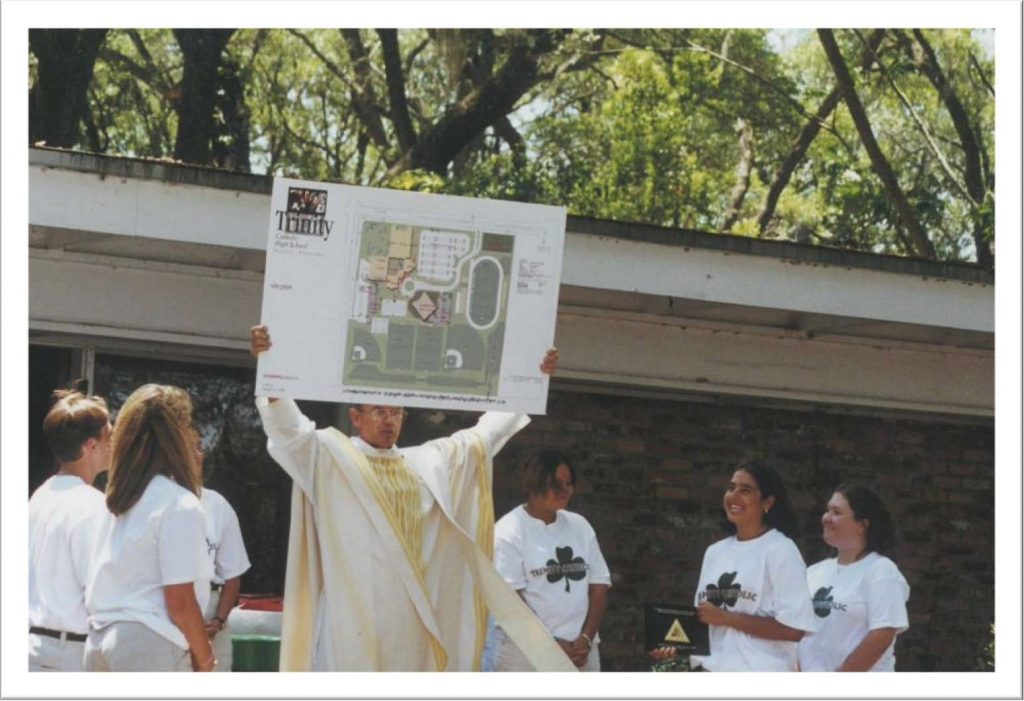

That changed in 1999. Then, the Most Rev. Norbert Dorsey, bishop of the Diocese of Orlando, endorsed building a Catholic high school in Ocala. Thus, in December 2000, Blessed Trinity Catholic Church broke ground for Trinity Catholic High School, which turned out its first graduating class in 2004.

Twenty years after its launch, Trinity Catholic reached a long-awaited milestone: Its “mortgage” was paid off.

The Rev. Pat Sheedy, Blessed Trinity’s pastor, said the high school’s overall debt to the diocese had topped $20 million.

Sheedy planned to host a mass at Trinity Catholic’s football stadium to celebrate by burning the mortgage. That’s been tabled until school resumes because of COVID-19.

Still, the coronavirus has not dampened the excitement of those who were instrumental in starting Trinity Catholic or those who continue its work.

“Everybody’s response in the Trinity Catholic community has just been very positive about this achievement, and it is an incredible achievement,” said Trinity Catholic President Lou Pereira, who noted that the school’s “community” also includes families from as far away as Claremont, Gainesville and areas on the Gulf Coast.

“It’s a breath of fresh air for people who are ardent supporters of the school.”

Sheedy, who has been at Blessed Trinity for more than three decades and a parish priest for more than 50 years, said he had never been in a parish that wasn’t connected with a Catholic high school.

Before Trinity Catholic, he recalled, the closest Catholic high schools were in Tampa, Orlando and Jacksonville. He cited two factors enabled him and his parish to make the case for a school in Ocala.

One was the increase in size of Blessed Trinity School. In 1989, the school began an expansion after its enrollment neared 250 kids. Today, it serves roughly 600 students.

Sheedy’s other selling point was the commitment of Trinity Catholic’s “founders,” or people who pledged money to build the high school.

“It was a great faith on their part. That’s my biggest thing from them,” said Sheedy, noting the founders ponied up even though the church did not have a site for Trinity Catholic.

Overall, those donors pledged $4.1 million before the project was publicly announced, according to a church document.

“We got between four and five million (dollars) from people who just believed that it was possible,” Sheedy noted. “I was always inspired by the first group that threw their hat in the ring. They just believed it was possible.”

The first believers to step up were the late Dominic and Fran Marino. They seeded the initial fundraising drive with $1 million. Over the years, as the high school grew, their total contribution bloomed to $4 million, Sheedy said.

The couple’s daughter, who is also named Fran Marino, and her husband, Steve Farrell, recalled that the Marinos originally came to Marion County as snowbirds from New Jersey, where they had created scholarships and made other contributions to their parish and its school.

Once settling in Ocala, their admiration for Sheedy led them to join the Trinity Catholic cause, Marino said.

But they were also motivated by philosophy, that of the school and of their faith.

“My dad was a successful man and he believed that people should aspire to be successful. But he was also very aware that not everyone had the same opportunities, and when Father (Sheedy) mentioned that he wanted a school where children could go regardless of their religion, regardless of their income level, I think that really spoke to my dad,” Marino said.

“I think he saw it as an opportunity for some families and some children who would never really get that chance for a good education and a Catholic education.”

Additionally, Marino said, “We are a very grateful family and we’re always very grateful and aware of our blessings. And I think it was a way for them to thank God for their blessings, and to give back, because that’s what we do. We believe in giving back.”

With the debt finally paid off, Marino added, “It’s a big endeavor, what they did, and they did it. And I think they (her parents) just would be glad for the community, in that the school had community backing.”

With the founders on board, the diocese eventually acquired 55 acres at the corner of Southwest 42nd Street and County Road 475A.

Besides the founders’ pledges, Sheedy said the diocese matched the church’s commitment dollar-for-dollar up to $2.5 million to obtain the land, and then floated an interest-free $10 million construction loan.

That total package, once all expenses were accounted for, topped $20 million, he said.

“What’s exciting to me is what happens at TC, because you can build stuff and it could be useless,” said Sheedy, adding that Trinity Catholic seeks to promote spiritual development and healthy social life along with strong academic and athletic performance.

“It’s a great option for people, apart from Catholics,” Sheedy said.

“When you have good schools, one feeds on the other, in sports and academics. It’s good to have good options for people.”

Twenty years ago, Trinity Catholic began as a group of portable buildings on a remote corner of Ocala. Today, it is a vibrant comprehensive campus that boasts top-notch academic, athletic and fine arts programs.

But Sheedy says paying off the debt to the diocese, which technically owns the school, is not a time to rest on laurels.

“My prayer would be that there would always be a great faculty there, great academics, great sports, great spirituality. Otherwise, what good is it?” Sheedy said.

But, he added, “You never sit back and say ‘That’s done.’ Because nothing is done.”

Pereira agreed.

He said the school is planning the addition of a fine arts auditorium.

Retiring Trinity Catholic’s debt will free up some resources for that, as well as provide funding for more mundane things such as installing a new school roof or replacing an aging air conditioning system.

“Now,” Pereira said, “we don’t have to think about the debt. We can now look to the future and not be harnessed by the debt, and make our little gem here in Ocala better and better.”