The “first” of the first responders

It’s time to honor our local 911 call takers and dispatchers.

Tami Hill-Lemus, a call taker and a Marion County Fire Rescue dispatcher, is silhouetted as she works at her station in the Marion County Communications Center at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office in Ocala on Friday, April 5, 2024. Editor’s note: The images on this page have been digitally altered to blur sensitive and protected text displayed on monitors, both in text and displayed on maps in the Marion County Communications Center. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2024.

Imagine picking up your phone to assist a woman experiencing a miscarriage. “She’s in the bathroom and she’s worried she’s miscarriaging.”

Or this: “I see smoke coming out of my neighbor’s roof.”

And it’s your job to send help, knowing every second counts.

Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, Marion County residents call 911 with their emergencies, both real and imagined. On the other end of the line are trained public safety telecommunicators (including call takers and dispatchers) who direct law enforcement, fire rescue and medics.

These unsung heroes are recognized annually during National Public Safety Telecommunicators Week, in the second week of April.

Starting April 14, the call center crews will be recognized for their selfless work. Both call centers individually have festivities planned to commemorate the National Public Safety Telecommunicators Week.

Sherry Gronlund, OPD’s communication manager, shared the “prom” theme to the city’s banquet plans with the “Gazette,” noting in her 24 years working in call centers, “Don’t ask me why, but I’ve found people in call centers usually like themes and they like to dress up.”

This year, the “Gazette” went behind the scenes at both call centers on four separate days to learn about those who have helped the county’s 911 operation earn the designation of an Accredited Center of Excellence by the International Academy of Emergency Medical Dispatch.

From two call centers—one operated by the Ocala Police Department and the combined communications center under the county based at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office—staffers work 12-hour shifts, 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. and 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. in the dark in front of multiple large computer screens.

When a call comes in, a prerecorded response starts playing immediately, introducing the call taker and asking for the address for the call. Administrators always want to have enough 911 call takers so no one waits for a response.

Each center has a large screen showing how many calls are being handled and how many available call takers there are at any given moment. If that screen indicates zero available call takers, it goes red and reminds everyone in the room that nonemergency calls need to call back on the nonemergency number, which the center also answers after prioritizing emergency calls.

Dispatchers watch the notes taken on the calls across the room and, depending on the call taker’s notes, can start dispatching law enforcement or the fire department to addresses while information continues to be gleaned from the caller. Marion County Fire Rescue responds to all of the medical related calls for the entire county because it provides medical transport.

In between their stoic, kind, but sometimes firm telephone conversations, the telecommunicators also take a lot of verbal abuse from callers. Some examples: “I pay for your paycheck; Do as I say!” In response to being asked for their address a second time, “Are you stupid? Do you have a hearing problem?”

And, yes, they have heard every expletive you can imagine.

Call takers can’t hang up on the caller. They aren’t customer service. They are a lifeline to people in distress, and they know people don’t all react the same under stress.

“There are no professional callers, only professional call takers,” said Kyle Drummer, the Public Safety Communications Director for the Marion County Board of County Commissioners.

A call taker and a Marion County Fire Rescue dispatcher, who only wanted to be identified by his first name, Nate, works at his station in the Marion County Communications Center at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office in Ocala on Friday, April 5, 2024. Editor’s note: The images on this page have been digitally altered to blur sensitive and protected text displayed on monitors, both in text and displayed on maps in the Marion County Communications Center. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2024.

Of course, the stress is not limited to just one side of the phone call.

Delia Beauvais, who has worked as a call taker for two and a half years at the Marion County Communications Center, said the support she gets from management and her teammates is what gets her through the tough calls.

“I had a really bad call my first two weeks. I think I probably would have quit if I hadn’t had their support,” she said.

But after handling one difficult call after another, Beauvais said call takers learn they have the strength to survive others. “You realize,” she said, “maybe I do I have it in me.”

“There is a rat in my house.”

“I want to report fraud. Someone is wiring me money and it feels suspicious, and I don’t want to get in trouble.”

“I’m going to commit suicide.”

Often, the call takers must coax critical details from frantic callers who don’t know what to say.

“Sometimes they are afraid to admit it’s an emergency and we have to pull it out of them,” explained Beauvais, following a call from someone asking how to get a restraining order.

Beauvais has had callers asking for practical assistance with an abuser nearby. “Sometimes it’s hard for them to admit they are under immediate threat,” she explained.

The call takers always ask for the address twice and their telephone number at the start of the call. Sometimes this annoys the caller, which was often obvious during the time the “Gazette” sat listening with the telecommunicators.

Nate, who requested that his surname not be published, has been a 911 call taker for Marion County for five years. He acknowledged that people often are annoyed but said, “Sometimes they realize when they say it again that they were confused the first time. In a stressful situation, an address is an easy thing to get turned around on. But we need the right one to get them help quickly.”

Both Ocala’s and Marion County’s call centers utilize a software program called ProQA, which guides the call taker through a list of medical questions to help them give the timeliest lifesaving advice to the person on scene and provides prearrival information to those traveling to the scene.

Sometimes, callers mistakenly become agitated by the medical questions and believe they may be delaying help. But the medics en route receive every answer the caller gives simultaneously.

After listening to a call from a granddaughter about a missing grandfather who was possibly being scammed from his home for money, Beauvais kept asking about any tracking features on his phone or vehicle. In that case, there were none.

But after the conversation, Beauvais told the “Gazette” that many of the call takers in the communication center track each other.

“I might have a dead phone, but they [her coworkers] may be able to see where I was last,” she said.

“I want to know how to get a restraining order against someone.”

“There has been an accident, we need medics now!”

“My neighbor just left their car in the road again.”

OPD’s Gronlund told the “Gazette” the department’s training entails months of intense practice before officials allow the call takers to work on their own. “And sometimes, even after that training investment, they can’t handle the pressure,” she said.

In order to find the perfect fit and always have personnel trained and ready to fill positions that come open, Gronlund said she’s interviewed people every week since she started in the department eight years ago.

Gronlund’s sentiment was echoed by Lisa Cahill, the Public Safety Communication Manager in the county’s Communications Center.

Cahill estimated it’s a $150,000 investment by the county to get each PST ready when factoring in the cost of the “trainer, the trainee, classes and certification fees.”

The county indicated they were staffed satisfactorily for the time being. However, the city indicated they’d like to add at least six more PSTs to their team. According to the city’s website, an entry level PST earns $40,000 a year.

Cahill, who is also the executive director of the Florida Telecommunications Accreditation Commission, told the “Gazette” that there is a shortage of PSTs across the country and agencies are also working hard at retention.

Team building is paramount for the leadership. A caring team is essential for making hard work a little easier for the call takers, who look out for each other as well as those calling in.

KarDasaty Davis, a nighttime 911 call taker supervisor at Marion County who has been at the job for five years, said although the calls can slow down at night and the center is quieter, “I know their [the 911 call takers] voices well so if I hear a certain pitch, I know to check with them on what is going on.”

Cynthia Hamilton, a 28-year-old call taker/county fire dispatcher, said the shared experiences help the team bond.

“When you are together 12 hours a day, under stress, and sometimes days on end if there is a storm, you end up close,” she said of her fellow 911 communication team.

The team and management look for opportunities to bring fun to offset the challenges.

Tami Hill-Lemus, a call taker/county fire dispatcher who has been in emergency communications for 11 years, invited the “Gazette” to return during the Christmas holiday season.

Hamilton said they do potluck meals on holidays and make stockings, host secret Santas, have ugly sweater contests and, rather than Elf on the Shelf, it’s Find the Grinch. She added that she is always willing to work night shifts because she doesn’t have children and wants to support her coworkers who want to be there for their families.

Beauvais, who lives in Gainesville and commutes 35 minutes to work, said she happily makes the drive for a job with a good environment, despite the hard work. “Environment is everything,” she said.”

Hamilton, who has sat across the same large room for eight, years, agreed. “We support each other,” she said. “And those 911 call takers on the other side of the room are tough.”

Holidays are challenging. First, staffers know they are missing out on important moments with their own families but also the calls can be more heart-wrenching.

“People call (feeling) lonely,” said Hamilton, adding some ask to be taken into protective care under the state’s Baker Act because they feel they might be a danger to themselves or others. “They don’t feel stable. Families are having domestic disputes because it’s the first time they’ve been together all year.”

Storms are another challenge because the communications center workers need to have their own families prepared to weather the storm but also plan to stay for days on end at the call center. When winds get too high to send out help, they still take emergency calls and prioritize who will get assistance first.

And after a storm, the county often sends a Telecommunicator Emergency Response Taskforce to impacted areas that need assistance.

“My stomach hurts.”

“There is a man outside our store asking customers for money so he can buy beer.”

“I want to place charges against someone who sent me a picture of their genitals.”

The call takers and dispatchers are everyone’s 911 team, even for those whose boots are on the ground responding to emergencies.

Cynthia Leedy works at her station in the Marion County Communications Center at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office in Ocala, Fla. on Friday, April 5, 2024. Editor’s note: The images on this page have been digitally altered to blur sensitive and protected text displayed on monitors, both in text and displayed on maps in the Marion County Communications Center. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2024.

Dispatchers Lemus and Hamilton expressed concern for patient care but also for the care of the first responders to whom they are providing directions.

“Their safety is a priority” when it comes to telling field unit personnel when to stage nearby and wait for law enforcement to secure an area in a volatile situation.

Through information secured through the 911 communications, the dispatcher can advise/equip/warn the fire and medical personnel, who are not armed, what to expect. This is important to know because in the “Gazette’s” experience reporting on dangerous incidents in Marion County, it is not uncommon for paramedics to arrive at scenes before law enforcement does, particularly in remote areas.

“There have been times when they come up to a scene and they tell me they are making the call and going in because the patient needs them now and they are using their discretion on the scene,” Hamilton explained, adding that those instances make her feel uneasy as she waits on the line.

The dispatchers also warn personnel about bad roads where rescue vehicles can get stuck so the first responders can take different equipment when they leave their stations. Hamilton showed portions of the county where there are either bad roads or sugar sand.

If it’s a fire, the dispatchers also start looking for water immediately. Their maps show all available hydrants, and when hydrants aren’t close to the fire, water tankers are ordered.

Dispatchers stay in contact with whomever commands the scene and if and when it’s time to get everyone out of a burning structure, those fighting a fire inside will hear the voice of the dispatcher telling them to retreat.

For the most part, calls for help within Ocala are routed to the OPD’s call center, from which personnel dispatch Ocala Fire Rescue and OPD officers. All the dispatchers are OPD employees.

There is a lot of overlap between what is dispatched from the city and the Marion County Communication Center not only because of incidents that occur in county enclaves within the city or incidents that happen on the city line but because the city relies on MCFR to send ambulances for every vehicle accident and medical call.

The two centers’ computer-aided dispatch systems “talk” with each other so that when calls come into one center accidentally, they can be transferred quickly.

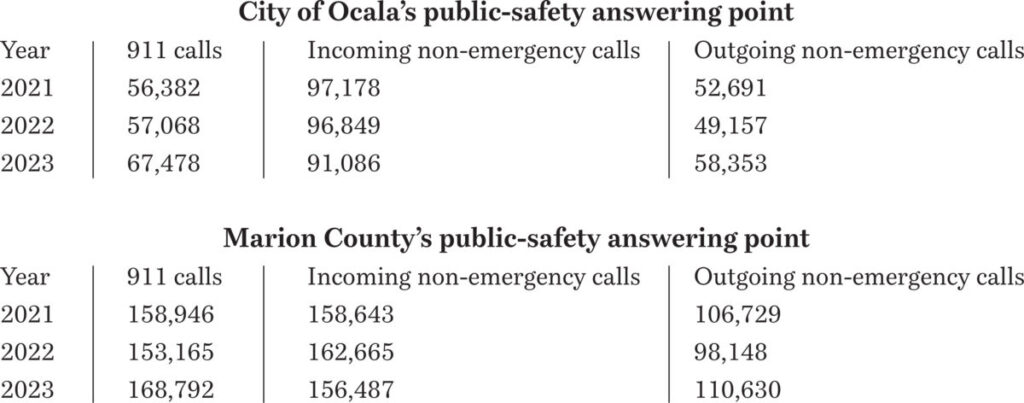

The city’s much smaller department of 34 call takers and dispatch personnel take 184 calls a day on average, whereas the county’s center of 63 call takers and dispatch personnel take 462 daily calls on average

For county 911 calls, the MCSO dispatches its law enforcement personnel from the same room where the county’s 911 calls come in. The county has dedicated fire department dispatchers, who break the county up into north and south when sending out field units.

Dave Searcy works at his station in the Marion County Communications Center at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office in Ocala on Friday, April 5, 2024. Editor’s note: The images on this page have been digitally altered to blur sensitive and protected text displayed on monitors, both in text and displayed on maps in the Marion County Communications Center. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2024.

Dispatch for fire and law are different in that law enforcement communications rely primarily on codes whereas fire communications utilize plain talk. Switching back and forth between the two types of conversations could be challenging, yet that is what OPD dispatchers are trained to be able to do.

Joe Cooley, a daytime shift supervisor at OPD who has been working for the department for nearly 10 years, recently dispatched police units in all four quadrants of Ocala while also supervising the other eight 911 call takers.

“My wife would never guess I could listen and multitask like this,” Cooley, a father of twin boys, acknowledged between dispatches.

The “Gazette” had a hard time following law enforcement dispatch because of the fast recitation of codes, but Cooley said their ears get trained to sort out certain words and codes. “Sometimes it’s hard with certain accents, though. I’ve been told when I get tired toward the end of a shift my southern twang increases,” he acknowledged.

Lauren Pozdol, a night shift supervisor who has worked for the department for six years, told the “Gazette” she was led to emergency communications after learning about the interesting role in true crime podcast.

Pozdol said learning everything in the beginning was tough but that good training over four months kicked in once she got in the seat. When asked how long it took her to become “comfortable” she quickly responded, “You don’t become comfortable per se; you become more confident with experience.”

For example, if there is someone suicidal on the phone, the ProQA system directs Pozdol to ask the caller why they have made that decision. “I always feel uncomfortable asking that one question because they don’t know me, it feels like I’m being intrusive. But I have to ask it,” Pozdol shared.

“This work is not like it’s depicted in the movies,” she added.