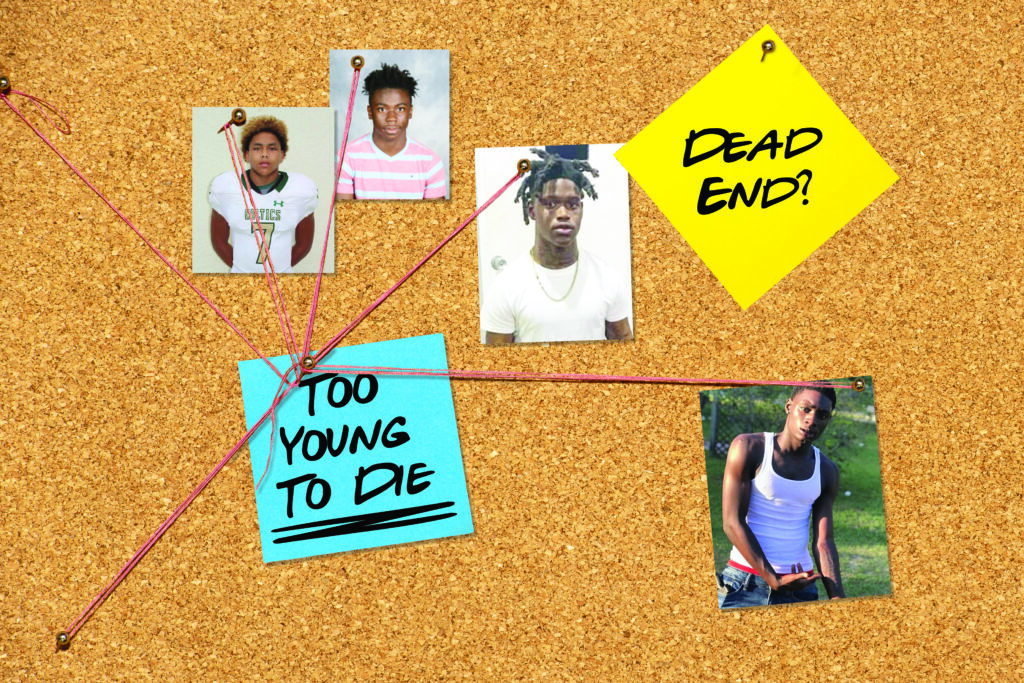

Silent Sorrow

Recent spate of teenage shootings points to troubling trend.

Jaydon Hodge drove Ky’Rion Weathers home from Forest’s football summer workouts on July 23.

“Remember to bring your paperwork,” he reminded Ky’Rion. “We’re going to be good this year. We’re going to shock the world.”

Ky’Rion, 15, was transferring from Trinity Catholic to Forest High School.

“I got you, Hodge,” he remembers Ky’Rion telling him.

It was the last time they would ever speak. Three days later, Ky’Rion was dead.

Ky’Rion died of a gunshot wound on July 26 at a home in Summerfield, making him the first in a spate of gun-related incidents among teenagers in Ocala in the last 11 months.

The domino effect

Almost a year later, Ky’Rion’s death is still under investigation by local law enforcement, said Rich Buxman, chief of homicide prosecution for the state attorney.

Jaydon Hodge, who is entering his senior year at Forest High School, said it’s frustrating.

“There’s different stories,” he said. “But no one is going to say it. No one is going to tell the truth… It’s going to keep on going. It’s going to be a domino effect.”

Five months after Ky’Rion’s death, Chris “Chevy” Chevelon was shot in broad daylight at Sutton Place Apartments on Dec. 6. He too was 15.

When Ocala Police Department officers arrived at the scene, a large group surrounded the Ocala teen as he laid in the grass, mortally wounded. However, most did not want to talk to police, according to a memo written by Buxman on May 17.

Lack of cooperation, according to Marion County Sheriff Billy Woods, is something that plagues law enforcement.

“Promise you, that if you look at them… parking lot full of people, they drive by and they shoot. Now out of 30 some people standing in the parking lot, there’s not a single witness. ‘I didn’t see anything,’” Woods said. “Well, you can throw the yellow BS flag on the table on that. Somebody saw something. Somebody knows who the shooter was. But they don’t cooperate.”

Following Chris Chevelon’s death, OPD took to Facebook to ask for the community’s help locating four persons of interest in the shooting. According to Buxman’s memo, they were able to talk to one person, only after he was arrested on an unrelated charge. He refused to speak to the police about what happened on Dec. 6.

Police will never get to talk to Kobe Bradshaw, another of the four they sought.

On June 5, Bradshaw, 18, was shot and killed near Northwest 62nd Place in the Ocala Park Estates Community at 3:45 p.m.

Investigators believe Bradshaw was involved in Chris Chevelon’s shooting, according to Buxman’s memo.

Conversely, investigators believe Chris was involved in a 2020 shooting that injured Bradshaw.

Bradshaw was shot at Tuscawilla Park last June 29. Chris’ name appeared on the incident report.

According to a witness referenced in the Buxman’s memo, he believed that “(Chris’) shooting was in retaliation … to Kobe being shot earlier in the year.”

Despite three teens killed by gun violence since July, shootings involving teens continue.

On Jan. 31, 18-year-old Omarea James, a Trinity Catholic football standout, was shot while leaving a gas station near 290 NW 113th Circle in Ocala. A bullet lodged in his spine, paralyzing the teen.

Nathaniel James Woodruff, 20, was sought by the sheriff’s office in connection to the shooting, as well as shooting at deputies during a pursuit on Feb. 2. Woodruff turned himself in to authorities on Feb. 5.

Recently, law enforcement agencies have responded to a triad of shooting incidents:

On June 6, the sheriff’s office responded to a double shooting at Whispering Sands Apartments, where two juveniles were transported to the hospital with non-life-threatening injuries.

On June 10, OPD responded to Parkside Gardens Apartments, where two minors were shot and suffered non-life-threatening injuries.

On June 12, the Belleview Police Department investigated a shooting near the 6800 block of Southeast 110th Street in Belleview.

Gang culture

In the wake of the recent shootings, some of which seem retaliatory, Woods and Ocala Police Chief Mike Balken have addressed the perception that the Ocala area might have a gang problem.

OPD investigated Chris Chevelon’s death, while the Marion County Sheriff’s Office investigated the death of Ky’Rion and Bradshaw.

According to Balken, while gang-related activity in Ocala doesn’t mirror what is shown on television, it is a problem.

“Well, we do have geographically… high areas of violent crime that are related to these groups. So, by definition, they’re a gang,” Balken said, adding that flying colors and flashing gang signs aren’t common in Ocala. “So again, not as visual in our community as it would be in LA… but certainly a problem we’re dealing with.”

Meanwhile, Woods is hesitant to label the area’s rival groups as “gangs.”

According to Woods, teenagers and other young adults form groups to seek a sense of belonging.

“When you’re young, you want to feel a part of something, and they form their little gangs. Does it meet the definition of a true gang? No, it doesn’t meet it,” Woods said. “It’s thugs out there that are coming together and going to do stuff together. Or it’s like the Hatfields and McCoys… where one group does something, the other one offends the other, and they retaliate against each other.”

But Balken and Woods agree the issue is a growing problem among the area’s young people.

“We’re arresting kids younger and younger for violent crime, for sure,” Balken said. “More often, obviously, than we’d like to see. So yeah, it’s a problem.”

According to Balken, by age 16 or 17, the state attorney’s office begins trying to charge violent juvenile offenders as adults.

But often, juvenile offenders aren’t given stiff punishment, and the more seasoned criminals exploit that.

“These crimes are being committed by juveniles, yes, absolutely,” Woods said. “And now, there’s adults in there in that process as well. And I’ll tell you what, the adults aren’t stupid… these criminals, okay.

“Because they know when it comes to a juvenile, they’ll convince a juvenile to commit a crime, knowing that they get into the juvenile justice system, get a slap on the wrist, and they get turned around and released. So that’s how the game works on their side.”

The vacuum

“On a personal level, I knew KD,” Jaydon Hodge said using Ky’Rion’s nickname. “He was a good kid.”

Ky’Rion lived with his mother Brittany and his younger brother Rontavious. And leading up to his death, his mother was expecting her third child – a little girl she named Briyani, which was the name Ky’Rion picked for his little sister, who he’d never meet.

But Ky’Rion’s father wasn’t around much.

And according to Jaydon, he’s seen the lack of a father figure affect teens.

“I think it’s the way they grow up and who’s surrounding them,” Jaydon said. “They need to have good role models. Most people don’t have father figures in their lives to guide them.”

Jaydon said he could tell when Ky’Rion’s lifestyle began to shift and got sucked into the vacuum of crime.

“You could see it. You could see it,” he said. “You could see he was trying to provide for his family.”

Before his death, Ky’Rion’s social media presence showed the teen’s growing interest in guns. Ky’Rion’s mother said she noticed her son and his friends’ growing interest in gang culture.

In April 2020, three months before his death, OPD pulled over a car carrying Ky’Rion, four others and two stolen guns. According to Ky’Rion’s mother, the teen cried when he went to juvenile detention.

But it’s not always the lack of a role model that causes some to fall into trouble, Jaydon said.

Other teens succumb to the pressures of society and their peers. He has seen several teenagers who come from supportive households fall into juvenile crime.

“I talk to them and ask them why they’re doing this,” Jaydon said. “You’re brought up good. Your parents care for you. You have a father figure in your life and your mother in your life. You know what I mean? But I guess they want to fit in. They want to be cool.”

The Forest High School safety has received offers to play football at seven of the eight Ivy League schools. He has also received offers to play SEC football at Mississippi State and Vanderbilt.

Despite societal pressures, Jaydon has stayed the path. But many don’t.

“A lot of kids are afraid to be different. You know what I mean? Because if I’m not doing what he or she is doing, then I’m going to be classified as weird because I’m not smoking, getting high or doing gang activity,” he said. “People gotta realize that it’s okay… it’s cool not to do that stuff. Does that make you different because you aren’t doing what they’re doing?

“Yeah, it means you’re not a follower. You’re a leader. They just have to separate themselves. They have to be different.”

Navigating dead-end investigations

According to both Balken and Woods, the use of intelligence-led policing has improved exponentially since the two began their careers in law enforcement.

Now, Balken said, law enforcement officials can use a scalpel to remove criminals from the community.

“We’re much better now than we were in years past at understanding that 10% of the people are committing 90% of the crime,” Balken said. “We’ve gotten much better at that over the last few decades and take more of a surgical approach.”

According to Balken, OPD responded to 18 confirmed shootings in six weeks earlier this year.

Confirmed shootings refer to incidents where someone or something was hit, casings were recovered, or some other evidence was collected.

“When we had that big uptick, we were able to go in and identify the key players, which were a couple rival groups going back and forth at each other,” Balken said. “We were able to quickly identify and target them specifically. Remove them from the streets, and then the shootings dropped off dramatically.”

However, just because OPD sees a rise and fall in gun-related incidents does not mean that Woods and the sheriff’s office see the same ebbs and flows.

In fact, according to Woods, when shootings are high in the city, they may drop in the county and vice versa.

“So, it bleeds over from cities into counties and counties into counties… so we kinda work together to pay attention,” Woods said. “I pay attention to what crimes they’re having because it’ll creep into our subdivisions like the Shores or Lake Tropicana. It goes into different areas into the county.”

And while patterns might vary between the city and county, the investigation process is largely the same for both agencies. And so are the obstacles that come with it.

According to Woods, a lack of cooperation from the community, witnesses and victims can completely upend an investigation.

“Well, we’re almost at a dead end. A lot of times, what we have left to rely on is the physical evidence… shell casings, if we recover the bullet itself,” Woods said.

Sometimes arrests unrelated to the incident are made, and the arrested individual is found to have a stolen firearm. In those cases, the weapon is brought back for a ballistics test and could potentially test as a positive match to a homicide.

“That’s like a needle in a haystack for us,” Woods said. “When you find that. That’s about our only avenues.”

For Balken, the lack of cooperation is frustrating.

“It’s unfortunate because the vast majority of these cases, we usually know who our shooter is. And through a lack of cooperation from the victims, those become very difficult to close.”

Bridging the gap

The reluctance to talk to law enforcement could stem from several things, Woods said.

Some could fear for their lives, he said.

For those who have those fears, Woods assures that there are measures to protect those who come forward.

Those assurances may not be enough.

“Sadly, in gang-related activities, if you snitch or something like that, obviously something bad is going to happen to that person,” Jaydon said. “That’s probably why most kids don’t talk to law enforcement when in reality they should.”

But fear isn’t the driving force behind the reluctance to speak to law enforcement, Woods said.

“Or people hide them,” Woods said. “They cover them up. Now, that’s not new to us. That’s always existed. You know, hiding a family member… keeping them from law enforcement and things.”

Occasionally, potential witnesses are a part of the same group or gang and therefore partake in the same types of criminal activities. This situation is so prevalent that when leads are dwindling, Balken and his force begin honing their attention on prolific offenders.

“When that occurs, we end up having to think outside the box and making a different approach and going after some of these more prolific, violent felony offenders in different ways,” Balken said. “So we’re looking obviously for illegal drugs, illegal guns… things like warrants and things like that and picking them up.”

Some people simply don’t trust law enforcement, something Woods says extends across all races.

“Mistrust that has been fostered over time, and I’ll go back to it, by parents, unfortunately,” he said. “And I’m here to tell you, that’s not any race specific. I tell people this all the time. I have the same problems in Ocklawaha, the Shores, the Forest, Lake Tropicana, Dunnellon, Reddick area… and race has nothing to do with it.”

What now?

According to Balken, grappling with violent crime is at the forefront of what he and his force do every day.

“I don’t want to say (we) allocate a tremendous amount of resources, but violent crime is violent crime,” Balken said. “It’s the most important thing we deal with. There is a large allocation of resources given to that.”

And between OPD’s jurisdiction and the rest of the county, there’s been plenty to keep both agencies busy.

Despite agencies actively working on several shooting incidents, Sheriff Woods assures that Marion County continues to be a safe area.

“Don’t fear. We are a safe community. Law enforcement here will protect them no matter what,” Woods said. “And typically, when we have these types of shootings and the violent crimes, it’s target-specific. Now, if you’re a bad guy, then heck yeah, you need to fear. You need to fear us.

“But if you’re a law-abiding citizen, it’s safe here in Marion County… I can tell you that.”

But for Jaydon, the latest spate of shootings hit too close to home.

“It’s hard. I wish we could change it just like that. But it’s going to take some leaders in the community to do that,” he said. “First off, we’ve gotta get these kids out of gang-related activities. Do sports or be productive in academics. You know what I mean? It’s going to be hard. I wish I had an answer for that too.

“We gotta gradually get closer and make a relationship with everybody. No matter what skin color, gender, law enforcement, no matter what your occupation is. We just have to grow as a community as a whole.”