“Missing students” befuddle, worry education officials

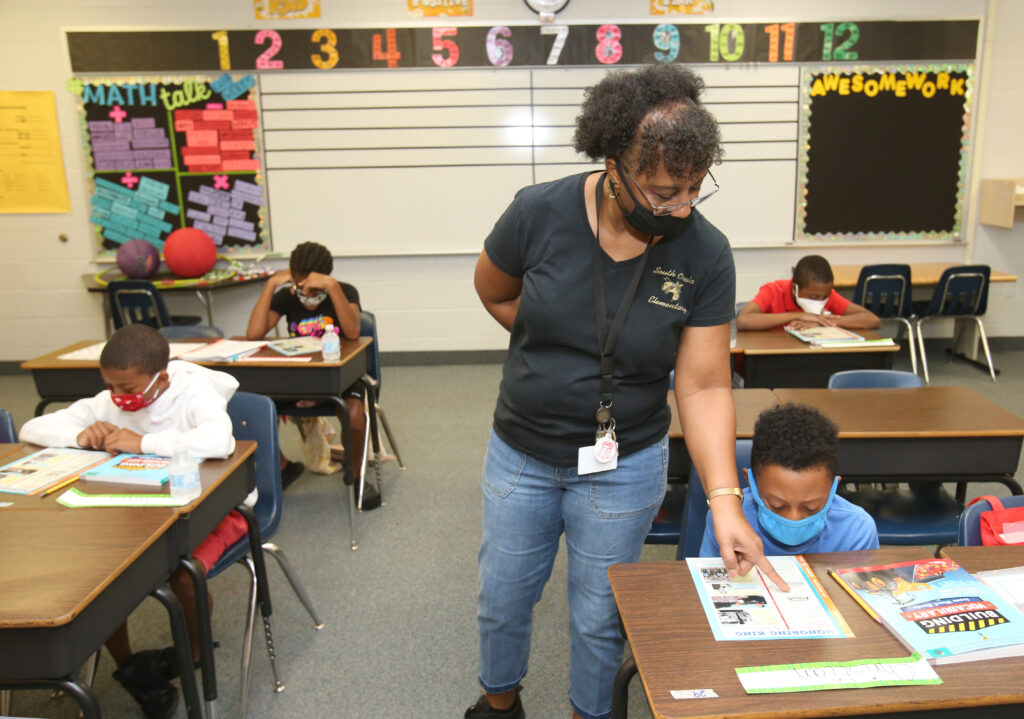

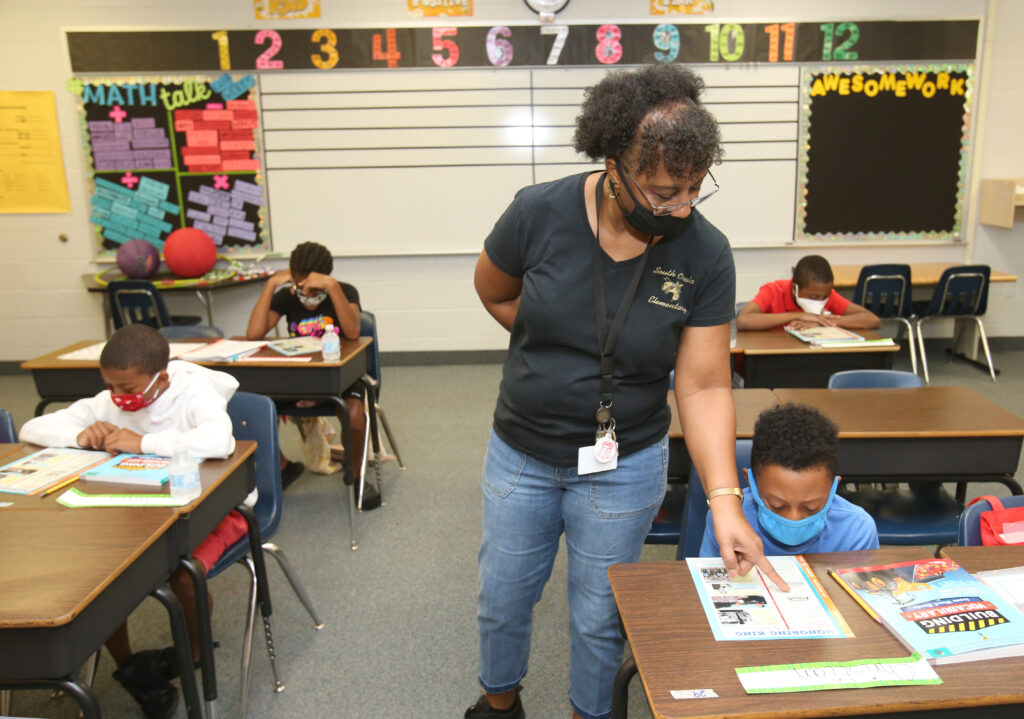

Carolyn King works with fourth and fifth grade students in her classroom at South Ocala Elementary School in Ocala in this July file photo. Student enrollment across the state and in Marion County is down amid the COVID-19 pandemic. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette]

Carolyn King works with fourth and fifth grade students in her classroom at South Ocala Elementary School in Ocala in this July file photo. Student enrollment across the state and in Marion County is down amid the COVID-19 pandemic. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette]

TALLAHASSEE – Florida legislators and local education officials are trying to pinpoint what happened to nearly 90,000 “missing” public school students, as public-school enrollment estimates have dropped amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

A mid-school-year estimate by state economists projects that 87,811 fewer students have enrolled in public schools than were predicted to sign up for the 2020-2021 academic year.

“Imagine a school district just closing. That’s the size of this problem,” House PreK-12 Appropriations Subcommittee Chairman Randy Fine, R-Brevard County, told The News Service of Florida on Feb. 1.

In Marion County, the latest enrollment count shows 1,705 fewer students than projected for the year. The Jan. 7 count showed a total of 41,191 student in the county’s 76 schools. The prediction for the year was 42,896. There are 811 less elementary students than expected, 245 less middle school students and 659 fewer high school students.

The Legislature’s Office of Economic and Demographic Research released the latest student-enrollment projection on Jan. 25, but it remains unknown how much of the drop can be attributed to students leaving traditional public schools for private schools or homeschooling.

“I hope it turns out that they’re all being homeschooled or in private school, and their parents just forgot to turn in a piece of paper,” Fine said, adding that he suspects a number of students aren’t being educated at all.

“We could have 9-year-old elementary school dropouts out there,” Fine told the News Service. “This will arc the course of their entire lives. Students are suffering enough because of the changes that had to be made because of COVID, some justified, some not. But to not go to school at all is a disaster.”

Student enrollment has an impact on schools’ funding, Fine pointed out to members of his committee during a meeting on Wednesday.

State Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran issued an executive order requiring schools to provide in-person instruction when the school year began last fall but allowed families to choose whether to send their children back to campus in person or sign up for remote learning. Under Corcoran’s order, school districts aren’t punished financially for students who don’t show up in person.

School districts typically are funded based on the number of students who receive face-to-face instruction. But, amid the coronavirus pandemic, Corcoran is allowing school districts to maintain funding based on their projected enrollment, as long as they provide in-person instruction five days a week.

But Fine suggested the state shouldn’t be paying for students who aren’t in the system.

“Schools are getting the funding for these 90,000 students who are not attending,” Fine told his panel.

Fine told the News Service that lawmakers have the authority to address the situation.

“We as a legislature could say, there will be no more phantom funding,” Fine said. “That will create an incentive on the part of the school districts to find these kids.”

State economists won’t know until the summer how many public school students might have gone to private schools or are being homeschooled.

Florida Association of District School Superintendents CEO Bill Montford said education stakeholders have a “moral and financial” obligation to find out where students have gone.

“About 88,000 fewer students showed up this year than what we had budgeted for,” Montford, a former Democratic state senator from Tallahassee said. “So, what happened?”

Montford, a former Leon County superintendent of schools, blamed the number of unaccounted-for students on “a multitude of factors, a lot of which centers on COVID.”

“We’ve got to dig into it district by district, to see where these losses really are,” he said. “It’s important for two reasons. One is, we absolutely have to know where these students are, not from a financial standpoint but more for their personal good. We’ve got issues like human trafficking and things like that that have nothing to do with school budgets. So most importantly, where are the children?”

The other reason why Montford said it’s imperative to learn where students have gone is budgetary.

“We’ve got to be careful when we budget for next year, because the way it works is, if there are less students who show up, districts don’t get the money,” Montford said.

Montford and some of the superintendents in his organization have a theory about the drop in projected enrollment. They believe kids they call “redshirt” kindergarteners may be sitting out their first year in school.

“We think that, out of an abundance of caution, a lot of parents said ‘I’m not going to send my kid to kindergarten’” during the current school year, he said. Instead, they’ll wait until COVID-19 infections begin to dwindle, he added.

Florida lawmakers have been considering the issue since committee weeks began in early January, in advance of the March 2 start of the 2021 legislative session.

School districts are now in the process of gathering their own enrollment information, the Legislature’s chief economist Amy Baker said during January’s education estimating conference.

Districts are being asked to submit information “in regard to enhanced outreach and … truancy and attendance,” as well as “anything they know from private school enrollment and homeschooling,” she said.

Baker said she anticipates the state Department of Education will send a memo to county school officials to inform them that the latest school-enrollment estimate “isn’t a typical forecast that they would get from us, but more of a platform or a baseline, and that they’re going to have a heavy lift to bring their 67 individual views into it.”