Law enforcement’s flawed social media policy hurts juveniles more than it helps

In 1994, when Florida legislators made an exception to the privacy of juvenile records if the minor was accused of committing a felony, the internet was in its infancy and social media was barely a programmer’s dream. It’s fair to say the legislators’ deliberations did not envision a day when local law enforcement agencies would have, in effect, their own unbridled online broadcast platforms.

During that same 1994 legislative session, the lawmakers created a new agency, the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, or DJJ, which is responsible for managing the juvenile justice system.

The new DJJ shared with its federal counterpart an intent to address juvenile crime with evidence-based programs to map out paths so that youths entering the justice system have the best chance possible of successfully rejoining society. That road map includes suggestions to agencies, based on evidence-based studies, that factor in the youth’s community of teachers, family, friends and neighbors.

The studies underpinning this approach include peer-reviewed research that reached some fairly common-sense conclusions: For example, kids who return to crime-ridden neighborhoods are more likely to get in trouble again, and kids with jobs are less likely to get caught up in crime.

The insistence on a collaborative approach among the agencies participating in the process ensures that methods established by data-driven evidence are used. This unified response aimed at the youth’s reentry into the community requires all involved to “think exit at entry” into the system, according to Youth.gov, a federal government website aimed at creating effective youth programs.

Fast forward to present-day Marion County, where local law enforcement agencies, without the support of any agency aimed at actually helping troubled kids and ignoring years of research into juvenile crime, continue a practice of digitally shooting first and asking questions later.

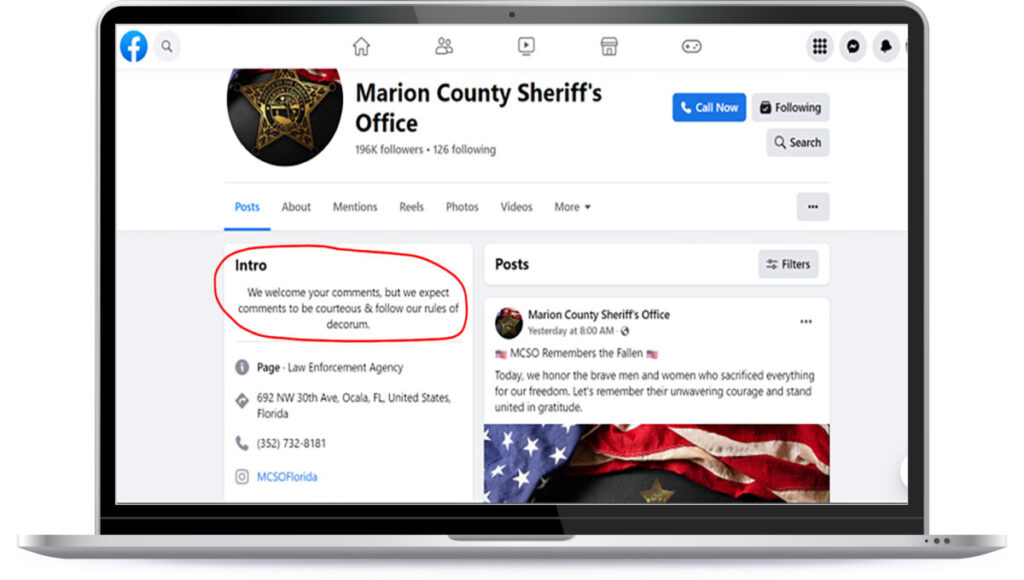

The agencies, led by the Marion County Sheriff’s Office, continue to post certain minors’ arrest photos and their names to their social media outlets within 24 hours of their arrest. MCSO and the Ocala Police Department are utilizing public records available to any citizen and placing the information on their online platforms, where they have built up a significant audience on the taxpayers’ dime.

How do they choose which of the approximately 1,000 annual arrest photos of juveniles to post? We don’t know; if there is a formula, the agencies won’t share it. Thousands of mug shots haven’t been shared over the past few years. How did those youths get a pass from the online firing squad?

Is the answer that they are only showing photos of minors who are being charged as adults or who are considered a public threat? The short answer is no, because these postings have been made shortly after the teen’s arrest and well before the state attorney’s office has made that charging decision.

For example, of the 16 juveniles whose arrest photos the MCSO has posted on social media since January 2022, some of youths as young as 13 and 14, only six subsequently have been formally charged as adults.

The most recent post by the MCSO earlier this month was that of a 14-year-old boy who allegedly used his BB gun to shoot his dog and posted a video of the attack to social media. The sheriff reported that the dog survived and received medical attention. Meanwhile, the boy was arrested on a charge of aggravated animal cruelty, and his arrest photo was posted.

Over 1,400 people weighed in on the arrest report on the MCSO Facebook site, overwhelmingly condemning the boy and his alleged actions. Many of the commenters said, in their opinion, the boy’s eyes in the photo showed no remorse for his alleged actions. Some even suggested that the sheriff may have successfully thwarted a future mass murderer. In what amounted to a social media lynch mob, the commenters angrily screamed through their keyboards all sorts of severe punishments they thought the boy should face.

Not all of the commenters followed the same thinking. One writer who claimed to know the boy’s family wrote that the boy and his siblings were following in the footsteps of their mother, who is incarcerated, and blamed their father for not doing a good enough job of parenting. The sister of the arrested boy said she needed to go on the MCSO Facebook page and defend her honor and that of her father, while insisting she would never turn out like her mother or act like her sibling.

The animal rights group PETA even weighed in, sending a letter encouraging the Marion County Public School district to teach kids not to be aggressive toward animals. Good advice, but off point here because the boy was not enrolled in a public school.

To be sure, we’re in no way condoning the abuse of animals under any circumstances. Even a cursory search online for “children who hurt animals” will reveal studies linking this dangerous behavior to even worse outcomes and experiences. For example, sometimes children will hurt animals after suffering trauma or abuse themselves.

In a written statement, the MCSO has defended its decision to post arrest photos of juveniles.

“We believe that parents deserve to know who their kids are hanging out with. Many parents know their children’s friends and acquaintances by sight but may not know their names. We hope that parents who see these posts on our Facebook page can use the information to help their kids make good choices about the people with whom they are associating. If one of their friends shows up here as having committed a serious crime, we hope that parents encourage their children to make that person a ‘former friend,’” they wrote.

The OPD did not respond to the “Gazette’s” inquiry.

The sheriff’s office could not point to any peer-reviewed research showing the impacts of law enforcement agencies posting juvenile arrest information on social media. There are, however, a multitude of peer-reviewed studies that have found that communicating to the community that a youth is unredeemable is detrimental to efforts to rehabilitate them.

For instance, a 2006 study published in the “Journal of Loss & Trauma” found that peer rejection during adolescence is itself a traumatic event. Additionally, a study by Purdue University in 2011 published in “Science Daily” said that if the one being ostracized feels like there is little hope for re-inclusion or that they have little control over their lives, they may “resort to provocative behavior and even aggression.”

“At some point, they stop worrying about being liked, and they just want to be noticed,” said Kipling D. Williams, a professor of psychological sciences involved with the study.

If the MCSO insists that publicly shunning these teens is the right approach, doesn’t the agency have a responsibility to follow up on these cases and tell the community whether the juvenile has been successfully rehabilitated?

Also, as a community, we need to ask ourselves how productive it is to pile on with comments against the accused, particularly one who is only 14.

We pointed out to the MCSO the lack of decorum in the public’s response to the post about the 14-year-old and asked if they would, at minimum, restrict comments on future similar posts. That way, when the accused teen or their family did read the sheriff’s post, they wouldn’t have to contemplate the sometimes insensitive comments from thousands of neighbors.

We received no response.

So, we bring it back to the community. How can we do better?

Imagine that boy is standing before you. Would you tell him his eyes are empty and unremorseful? Would you share a prediction for his violent future? Would you tell him his parents are bad? Would you throw him away?

Or would you ask him why?

Our juvenile justice system isn’t perfect but, thankfully, it includes people who investigate the why. And then, when no remediation is available, we have prosecutors and judges who issue judgments after knowing all the facts.

Let’s call it the civilized approach. And let our sensible actions speak louder than the ugly, and unhelpful, online hatred.