How Marion has kept its COVID-19 numbers low

A registered nurse with the Department of Health tests Steven Verdejo Jr., 16, for the coronavirus during the COVID-19 drive-thru testing at the Florida Department of Health Marion County in Ocala, Fla. on Monday, June 29, 2020. The Department of Health is testing for COVID-19 three-four days a week with prior appointments. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2020.

The number of new COVID-19 cases in Ocala/Marion County has jumped sharply in recent weeks.

Yet the community remains among Florida’s best at avoiding the ravages of coronavirus, according to state data.

As of July 1, Marion County reported 727 total coronavirus cases, with 477 added just since June 1, state Health Department data show. But as of last Wednesday, just 10 people, all county residents, had died.

That translates to a fatality rate of 2.8 deaths per 100,000 people. Comparatively, the statewide rate is 16.7. And for a wider contrast, New York’s rate was 165 per 100,000.

Meanwhile, Ocala/Marion tracks with the state in other critical metrics. For instance, the community’s hospitalization rate is 9.7 percent, compared to 9.3 percent statewide. And Ocala/Marion County’s positive case rate in long-term care facilities, such as nursing homes, where residents are most vulnerable, is 7.5 percent. Florida’s overall rate is 8.6 percent.

Any increase in deaths, hospitalizations or positive tests tends to focus attention on what may have gone wrong.

Yet those same numbers can also illustrate what was done right.

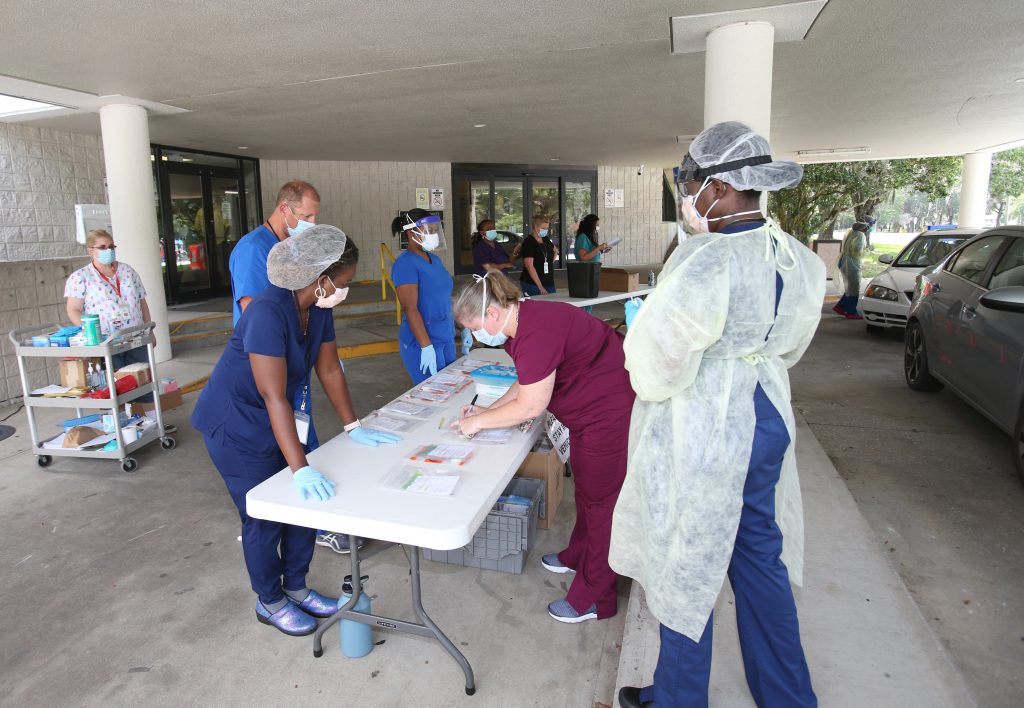

A registered nurse, who only wanted to be identified as Vanessa, left, and Triscia Swineheart, a health support worker, right, collect samples from people during the COVID-19 drive-thru testing at the Florida Department of Health Marion County in Ocala, Fla. on Monday, June 29, 2020. The Department of Health is testing for COVID-19 three-four days a week with prior appointments. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2020

In a recent interview with the Gazette, Mark Lander, administrator of the Marion County Health Department, identified several factors that have helped reduce the impact of COVID-19 locally.

Distance, in varying forms, was critical among them.

First, there was social distance.

“We were very fortunate when it came down to the mitigation practices at first. I really felt like we did a good job with the social distancing, and there were some things that were enacted early on which eliminated a lot of the social areas where people could hang out and get that close contact,” Lander said.

Those other steps included people wearing masks in crowded areas, such as retail stores, canceling large gatherings and closing bars and restaurants and recreation facilities.

“And we were actually adhering to those practices,” Lander noted. “By having that type of social distancing, we limited the availability of the spread.”

But Lander noted Ocala/Marion County benefitted from a different kind of “distancing” — to wit, having a broadly dispersed population.

“One of the advantages of Marion County is we are more spread out,” he said, noting that a light population density, relative to severely affected epicenters like New York City or even South Florida, helped Ocala/Marion County curtail the spread of COVID-19.

Kristina McClellan, a registered nurse, left, gets her face shield disinfected by Cece Bellot, a registered nurse, right, during the COVID-19 drive-thru testing at the Florida Department of Health Marion County in Ocala, Fla. on Monday, June 29, 2020. The Department of Health is testing for COVID-19 three-four days a week with prior appointments. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2020.

Distance was important in one other way.

As the coronavirus took root, Lander and his team had the advantage of watching how other communities reacted and what health experts learned from that.

“When you saw what was going on across the country, and even in Florida in some of the impacted areas, where they were started to get the cases when we only had a handful, that brings it home,” Lander said.

Consequently, Lander said the agency could understand the effects of interstate and overseas travel and close contacts.

“They did a really good job on the contact tracing,” Lander said of his own staff. “We were able to get those secondary contacts, and while some of those may turn positive, their contacts didn’t. We did not see a lot of that secondary spread after that close contact.”

Lander also maintained that unlike other places, Marion County, like the state as a whole, paid closer attention to what has shown to be the most susceptible areas: the roughly 50 long-term care facilities like nursing homes, assisted-living facilities and rehabilitation centers.

“Really before they had enacted a lot of the regulations and requirements for monitoring, dating back to mid-March, we had started calling our facilities on a daily basis, verifying client status, verifying worker status,” he said. “That’s been a success, and the state of Florida has done a really good job with those long-term care facilities.”

But, he added, much of the county’s older population, such as residents in many 55-plus communities, stuck to the recommended preventative practices and aggressively sought the Health Department’s input to learn how they could protect themselves.

Members of the Department of Health test people for the coronavirus during the COVID-19 drive-thru testing at the Florida Department of Health Marion County in Ocala, Fla. on Monday, June 29, 2020. The Department of Health is testing for COVID-19 three-four days a week with prior appointments. [Bruce Ackerman/Ocala Gazette] 2020.

The Florida Department of Health reports that people 65 or older comprise 85 percent of the 3,550 COVID-19 deaths in the state, even though they represent just 16 percent of all cases.

“What we’ve seen from those communities, at least from Marion County’s perspective, is that they were very compliant when it came to the mitigation recommendations,” Lander said. “The message was going out and they were being very, very proactive.”

Representatives of those areas, Lander said, wanted to learn about best practices for sanitation, “what-ifs,” how positive cases were handled, among other details.

One initial drawback was a strict limit on testing. The department lacked testing supplies and lab capacity to get results. It was not until around May 1 that the department was able to provide tests on demand. But demand has faded over time, such that the department has scaled back from testing five days a week to just two now.

Lander suggested that Florida, in fact, may have done so well at controlling the spread that coronavirus fell off the public radar, and it has only recently popped back into the collective consciousness as reports of a rising number of positive cases emerge.

But while the community and Florida have erected a relatively effective firewall against COVID-19, Lander is concerned as Ocala/Marion County sees more cases of late.

“I’m not discouraged (about the future), but our future is focused on testing and education,” he said. “It is a novel virus, and they learn more about it every day.”